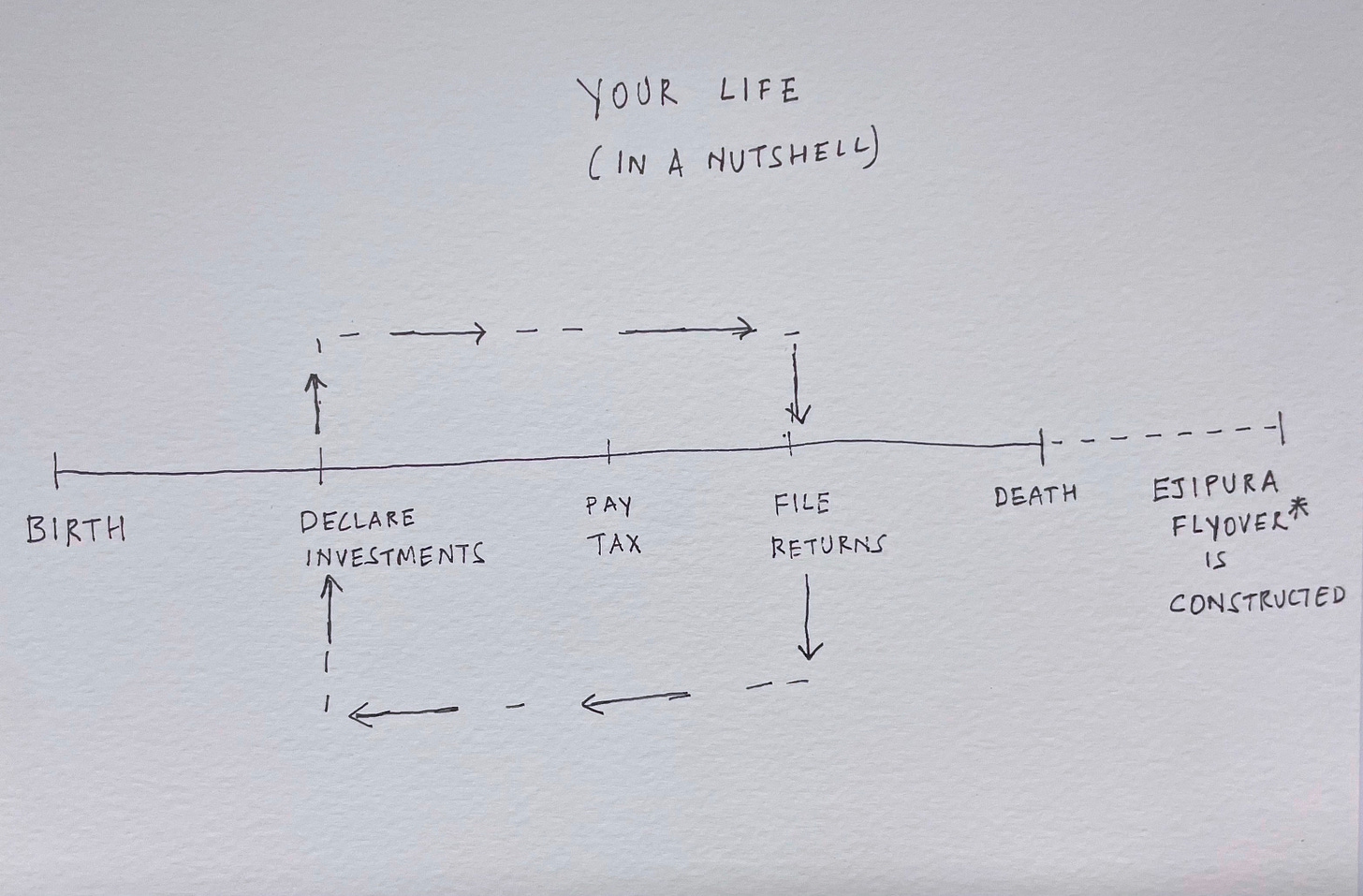

Why we understand time wrong

and how understanding it right will help us deal with regret, guilt and grief

It’s the end of 2024, and you’re either trying to wind up work or worrying about Secret Santa, trying to find the generic but not too generic gift for a colleague you barely know. You’re sitting down to reflect on the year gone by, and your inbox is filled with automated ‘Out Of Office’ replies with people gallivanting to picturesque parts of the world, trying to squeeze out the last bit of joy and leisure time from yet another year that has seen you swing from ecstasy to despair. You think of THAT week when everything on the CXO’s pet project went south, but you somehow managed to hold fort and salvage things. You think of THAT week when all your work over months on end on another critical project gave spectacular results (Admit it, you were surprised yourself).

You bagged that coveted promotion, but in this job market, it came with no salary hike, just a pat on the back, and a promise of taking care of things in the next appraisal cycle. It felt bittersweet - like how a migrant to a big city feels about their hometown - Too small for their shoes, and yet, still big enough for their heart. You remember the time you first left home, embarking on a future you knew nothing of, following a template set out by your parents. You moved to another city for education, and in turn, got educated about life. Power cuts, annoying landlords, and blocked kitchen sinks felt like inconveniences from hell. Your thoughts drift to how far you’ve come, from when you walked in as a nervous fresher, not knowing a thing about the corporate world. Your first piece of work had feedback that had more redlines than your puny little self-confidence could take, but just enough redeeming bits for you to soldier on. You found likely allies in fellow freshers, and an unlikely one in that one senior who always smiled and had encouraging things to say, whose words felt like a hug from an elder brother. Not even the system could break him. He gave you hope.

Soon enough, your redlines gave way to more work of the same kind, because you became good at it. It had the drudgery that defines modern jobs. And at some point, you couldn’t take it anymore and jumped ship. Since then, you’ve moved from one job to another, sometimes switching roles within the same company, sometimes sectors altogether. You moved up, managing people, swinging between looking out for yourself to feeling responsible for your team’s growth, and on most days, it felt like walking a tightrope, knowing that there was only so much you could control. You were the pigeon on some days, but on most days, you were the statue.

So as the salary ping of your bank balance became sweeter, your wants became your needs. You started buying things that made you feel you’d arrived, you went out eating and drinking at the plushest places in town, and you crashed at places of people who were mere acquaintances, feeling intrinsically safe on the premise and promise of second-degree friendships. You went from being that bewildered young kid out of school to being the confident adult crossing each milestone with aplomb.

But with it came the greyer side of life. Heartbreaks, which in the moment, felt debilitating. Friendships, which shattered under stupid misunderstandings. Hobbies, which were sacrificed at the altar of ambition. Careers, that betrayed us, even though they were never our choices to begin with. Money went from being a slave to a master, and even the most mathematically challenged amongst us, ran accounting software in our heads, knowing that we needed to stretch the rupee. The present felt secure, the future forever uncertain. But it was the past that weighed heavily.

You carry the unseen burden of regret, guilt and grief.

Regret for the things you did not do, Guilt for the things you did, and Grief for the things you lost.

And the regret, guilt and grief for the life you did not live.

The life you could have lived.

If you feel like this, there is a fundamental shift you (and I) need to make.

The way you think about time. Because your thinking about it may be wrong.

The Linear Nature of Time (or NOT)

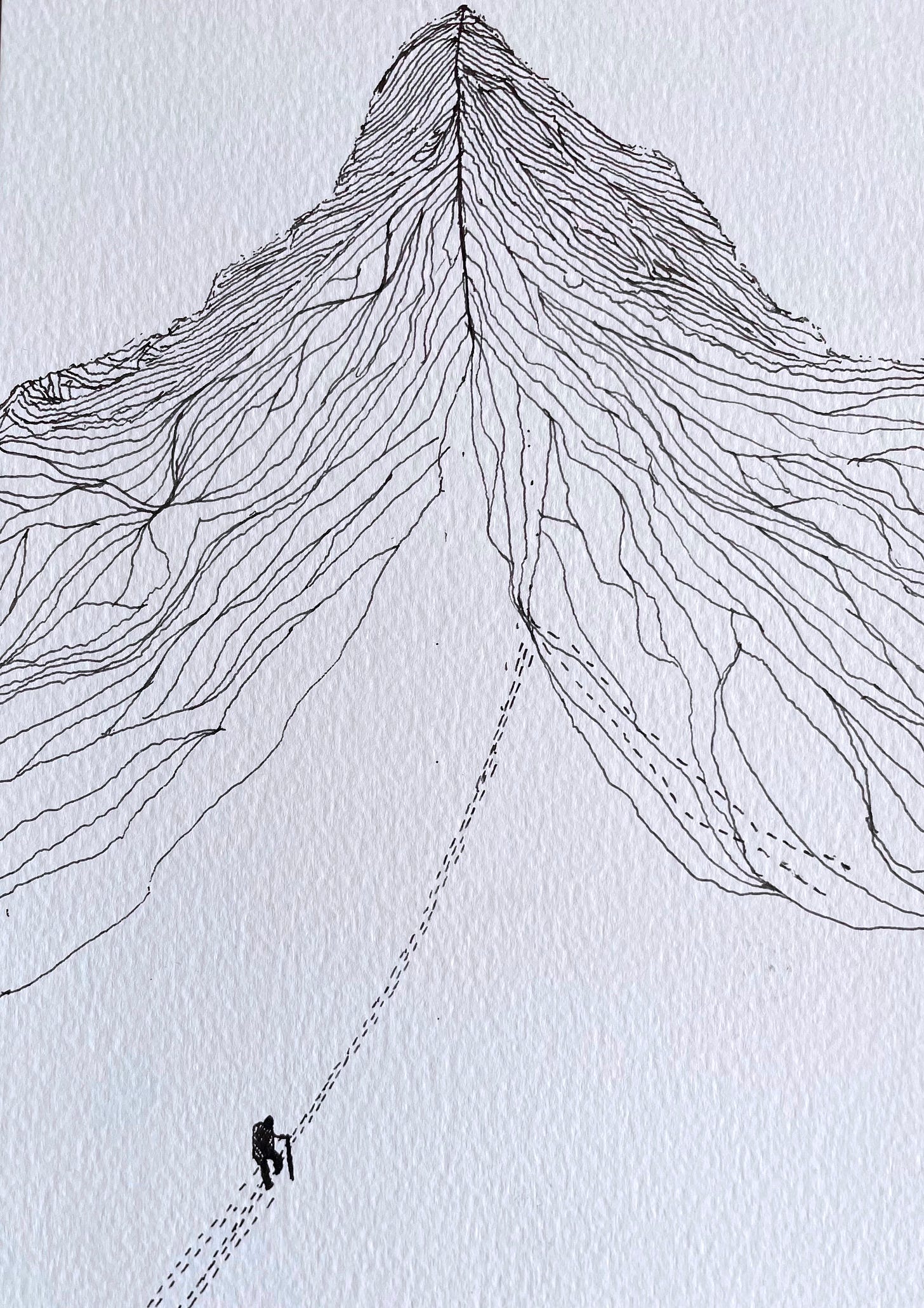

You conceptualise your life as a voyage. You think of yourself as a traveller. You navigate hostile terrain, unreliable friends and hospitable enemies. Somedays you feel like a nomad, unmoored, building settlements as you move, only to uproot them later. Somedays you feel like a merchant, never staying longer than a night anywhere, carrying out your business everywhere.

You take calculated risks, seize the moment, and push yourself harder than you did the last time. You treat each milestone as an invitation to up the stakes. Scientists have a term for it, Shifting Baseline Syndrome. Sure, it’s about our acceptance of environmental degradation. But you have anyways adapted it to your life too.

You imbibe the spirit of Citius, Altius, Fortius (Faster, Higher, Stronger), forgetting that what fits the Olympic games perfectly is a disastrous fit for everyday life. You run the marathon of life like a 100-metre dash. You are more breathless than Usain Bolt, and more tired than Eluid Kipchoge. And yet, you continue to run.

And each time you fail, it hits you hard. Your self-worth nosedives. You question your intellectual abilities, as your impostor syndrome paints the town red. You become mildly paranoid about your mental faculties and your ability to deliver results. You feel a strong sense of the Spotlight Effect, and suddenly feel that all eyes are on you.

Instead of your efforts, you become your outcomes. You feel miserable, cornered and hopeless.

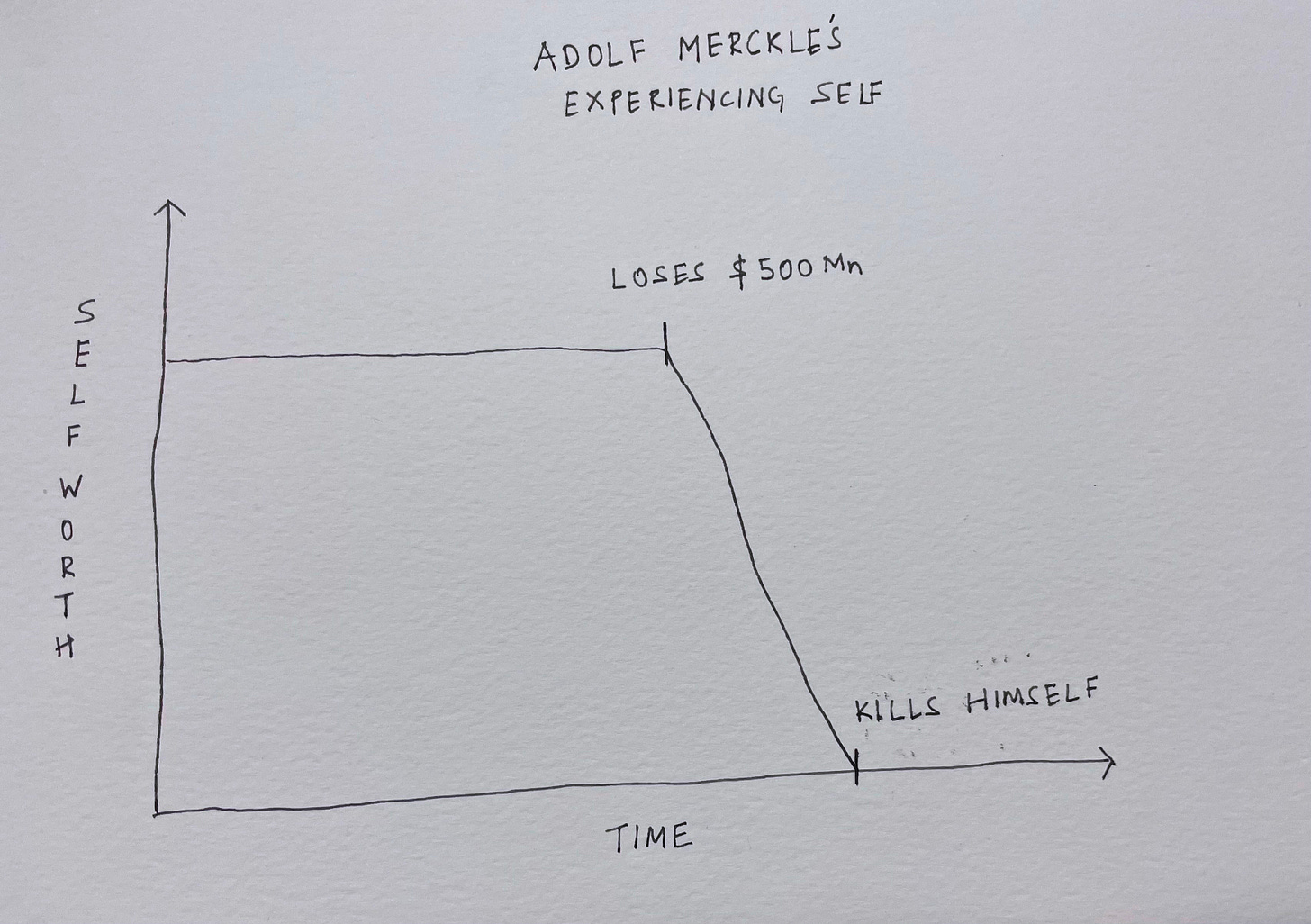

In 2009, this is how Adolf Merckle must have felt. He was a German billionaire who was among the 100 richest people in the world. He had an estimated fortune of $9.2 billion, and his businesses employed over 100,000 people.

Despite a track record of proven successes, Merckle made a series of disastrous bets during the 2008 financial crisis, resulting in losses that amounted to over $500 million. As the future of his business empire lay in question, he decided that being alive to witness its reversal wasn’t worth the mental cost.

On a cold Monday evening, he wrote a final note for his family, and took his own life in the most dramatic of ways:

By standing in front of an oncoming train.1

What the f**k just happened?

Here is what may have happened. And to understand it, we need to understand the concepts of Experiencing Self and Remembering Self (first proposed by the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman)

The Experiencing Self is the part of the mind that is in the present moment, responding to life as it happens. It's fast, intuitive, and unconscious, and focuses on the quality of the experience.

Adolf Merckle’s Experiencing Self saw his self-worth, reputation, intelligence, and financial judgment tank. So intrinsically his identity may have been linked to his wealth, that it felt like he was at a point of no return. He must not have felt like running anymore. It broke him.

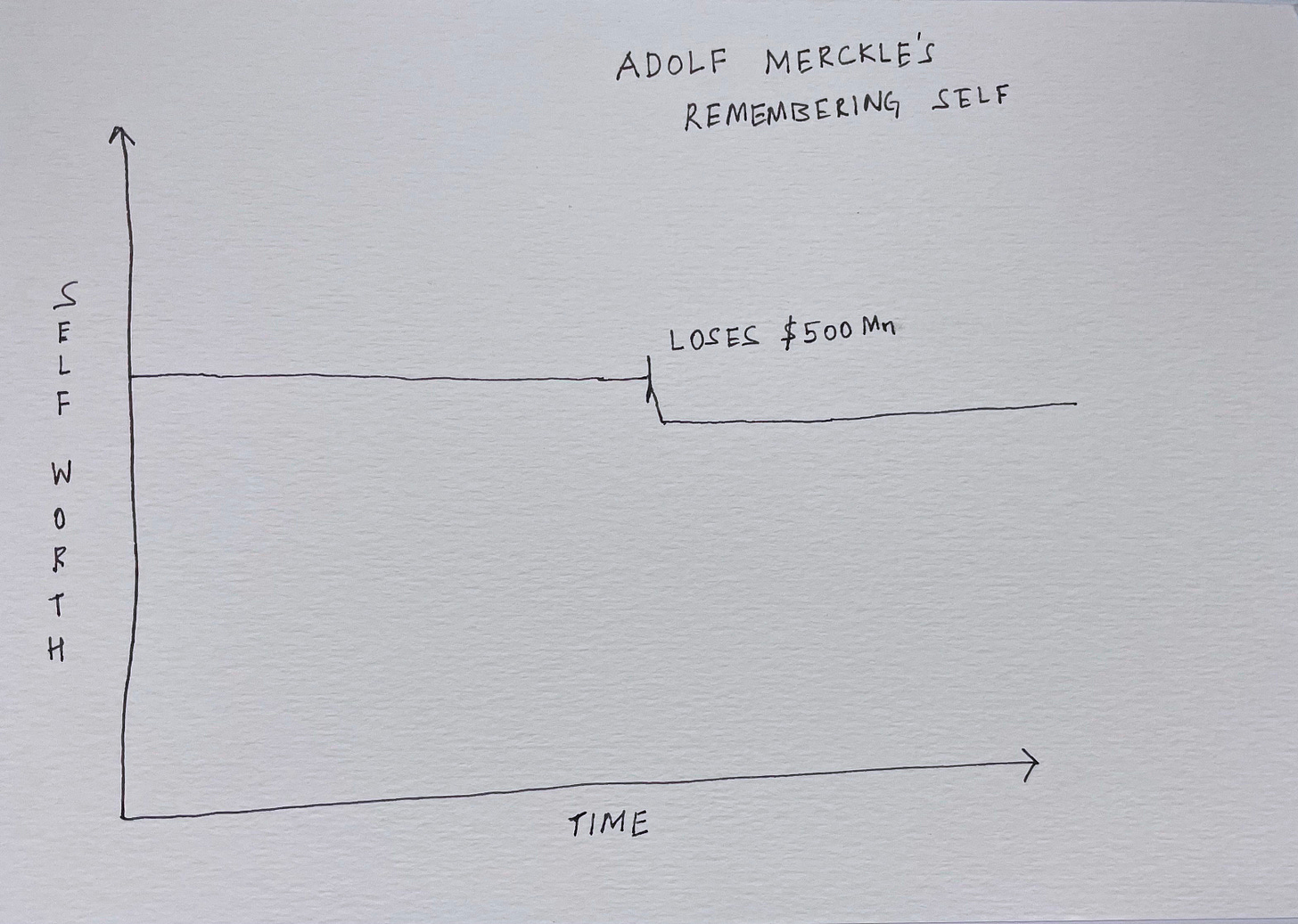

Adolf came from Swabia, a cultural region in southwestern Germany, which boasts Stuttgart as its cultural capital. He represented the Swabian ideal (or stereotype depending on who you ask in Germany) - frugal, clever, entrepreneurial and hard-working. Though he lived a quiet life, with mountain climbing being one of his enduring passions, I wish that in the moment, Adolf would have let his Remembering Self take over.

The Remembering Self is the part of the mind that looks back and reflects on experiences. It's slow, rational, and conscious, and tells the story of the experience. Had Adolf let his Remembering self take over, things may have turned out differently. Because then he would have remembered how he took over a family company with just 80 employees in 1967 and transformed it into a vast corporate empire of 120 companies ranging from pharma to cement, that generated revenue of some €30 billion. The $500 million loss would have felt like a detour.

As Kahneman puts it

"The Experiencing Self is the one that answers the question: 'Does it hurt now?' The Remembering Self is the one that answers the question: 'How was it, on the whole?'

And since our conception of time is linear, we often let the experiencing self sit in the driver’s seat. We perversely interpret the advice of ‘Living in the moment’ as giving incredible importance to the moment, experiencing it intensely. We forget that ‘Living in the moment’ actually means experiencing it thoroughly to reflect on it in its totality later.

So if the linearity of time is not the best way to think about it, then what is?

Some part of the answer may lie in the work of Wisława Szymborska, the Polish poet who was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996. As the Nobel committee conferred the award upon her, they noted that she was receiving it ‘for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality’.

One of her poems, Nothing Twice has the following lines

Why do we treat the fleeting day

with so much needless fear and sorrow?

It's in its nature not to stay:

Today is always gone tomorrow.

When I encountered these lines for the first time, I connected the dots with the writing of another Polish author, Olga Tokarczuk. In her novel, Flights, which is a rumination on modern-day travel (it won the Man Booker International Prize in 2018), she makes a brilliant observation.

When we see time as linear, it means that all that we have experienced, and all that has changed is irreversible. And because of that

Loss and mourning become daily things.

The answer to the alternative view of time dawned upon me in the sub-zero temperatures of Kashmir.

The Circular Nature of Time (or MAYBE)

In the 3rd week of December, every conversation I had with a boatman on a Shikara, taxi drivers, homestay owners, and servers in restaurants did not fail to mention one thing.

Chillai Kalan.

It is the local name for the 40 days of harsh winter in Kashmir. It is the coldest part of winter, starting from 21 December to January 29 every year. It is followed by a 20-day long Chillai Khurd (‘Small forty days of cold') that occurs between January 30 and February 18, and a 10-day long Chillai Bachha ('Baby forty days of cold') which is from February 19 to February 28.

The first day of Chillai Kalan is celebrated as Pheran Day, a loose woollen robe worn by Kashmiris to protect themselves from the cold. A trusted companion emerges, who walks with Kashmiris wherever they go. The Kangri - an earthen pot woven around with wicker filled with hot embers, and carried inside the pheran to provide constant warmth. Keeping in line with the Indian idea of heating and cooling foods, Kashmiris start their day with Harissa, a delectable mixture of sheep legs and rice flour, cooked overnight with a carefully measured mix of fennel seeds, cinnamon, green and black cardamom, cloves, crispy fried Kashmiri shallots and salt. It’s eaten with Kashmiri flatbreads like Kander Tchot or Lawassa and is considered to be a heating food, and therefore cooked and served only in winter. The Dal lake in Srinagar freezes over, and the pace of life slows down considerably. Communities huddle up in local mosques, where the warmth of hammam rooms - spaces with a burning hearth in the middle - keeps them cosy. People stay indoors, and hone their crafts - Everything from carpet weaving to walnut carving thrives during this season, when there is little else to do.

Temperatures routinely plunge below zero, but the average Kashmiri is not bothered. If one were to go anywhere in the Himalayas, the change in temperature and seasons is acknowledged but not fretted upon. You will rarely find people complaining about the weather like we city dwellers do, even though people in the mountains have fewer resources to deal with it.

Because at the heart of it lies the idea of acceptance. Of the cycle of seasons and life. Every Kashmiri knows the cycle of Chillai Kalan —> Chillai Khurd —> Chillai Bachha. The ready acceptance of seasons comes from the predictability of change. The assurance of spring and summer. The assurance of apple trees being laden with fruits. The assurance of the Dal Lake melting, and making way for the floating vegetable market again.

The best example of this acceptance comes from observing the Black Kite. During winter, it sits on the bare branches of Chinar and Deodhar trees, constantly scanning the horizon for prey. The trees are so bereft of leaves that you can easily spot its nest, appearing as clumps of twigs and sticks. Their flight is buoyant; they glide effortlessly and change directions easily. They will swoop down with their legs lowered to snatch small live prey, fish, household refuse, and carrion.

But the most interesting part is how they migrate.

They migrate thousands of kilometres away to the Altai mountains in Mongolia. But many of them choose a longer route instead of flying through the Taklamakan desert and China’s Tian Shan mountain range, where they would have to fly long distances in freezing weather. They choose to fly through eastern Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, to reach the same destination.

As governed by nature, they take a route that gives them a higher chance of survival. And that is common to people living in the Himalayas and raptors like the Black Kite.

Because those who see time as seasonal and circular are familiar with an immutable truth of life

Nature decimates your ego.

It humbles you, not in the way a high-on adrenaline boxer pummels his opponent. But in the way a kung fu master, gently but surely, tires the student with the simplest of tasks, repeated endlessly.

Those who see time as circular, find comfort and acceptance in its fundamental nature.

I first encountered the idea of time as circular when I read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. The book can be read as a linear progression of events or a repetition of the names and characteristics of the Buendia family. At the time, I thought of it as a brilliant storytelling technique, and I was unaware that the idea of time as circular exists in communities across the world.

But the circularity of time sits uncomfortably with me. If nature pre-determines so much of my life, am I less in control of it? Am I resigned to fate, and the Indian idea of “Jo jo jab jab hona hai, so so tab tab hota hai” (Whatever is designed to happen, will happen)?

Is this the kind of acceptance I am willing to accept?

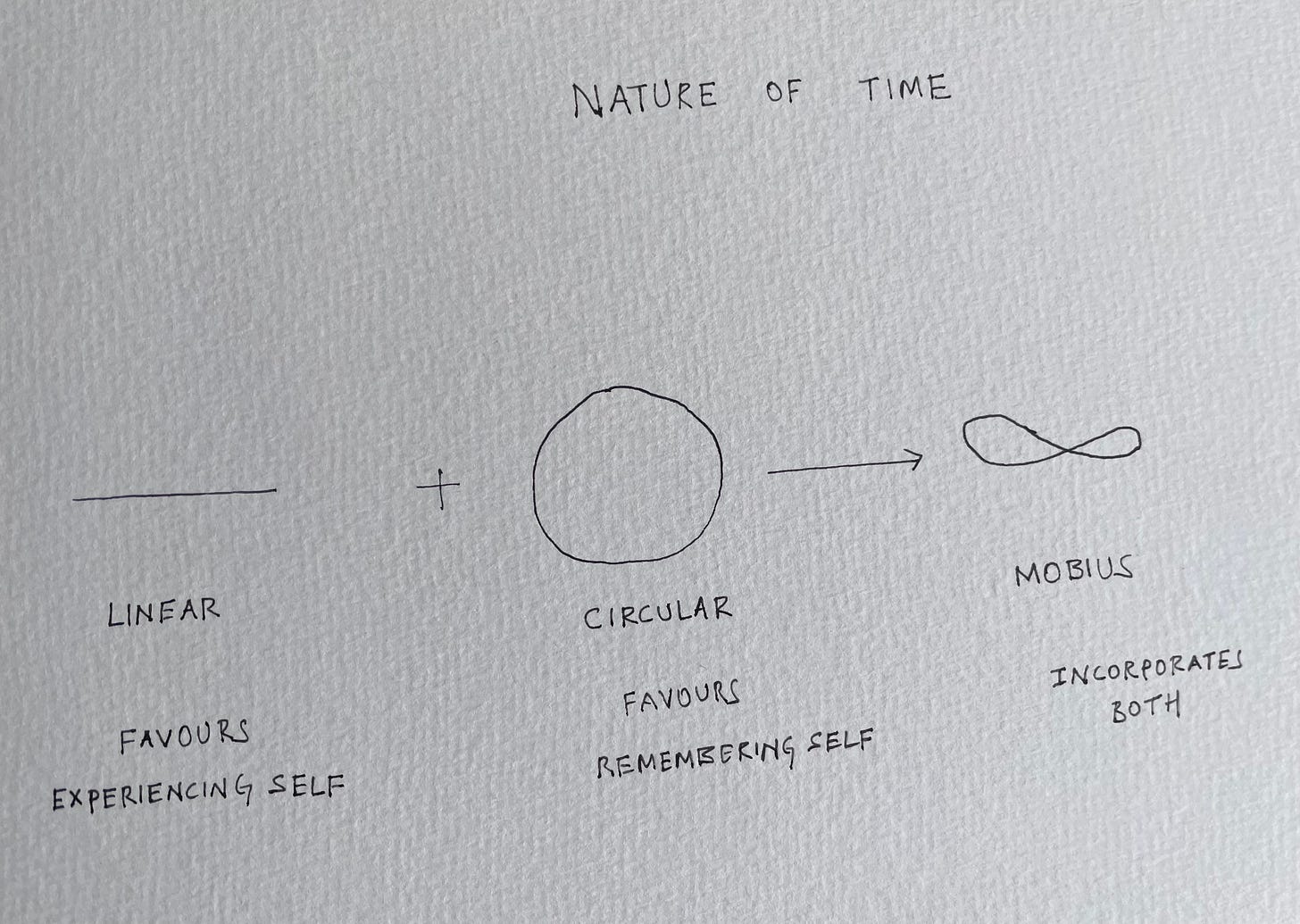

Maybe time is linear, and it’s circular at the same time. If that were true, what would the nature of time look like?

To understand that, we will take a short mathematical detour. Wait, don’t leave! I assure you that I have no intention of bringing back the horrors of Integral Calculus (or Engineering Mathematics II if you cried through your engineering education). This is the kind of math you wish you were taught. Because even your five-year-old will understand this.

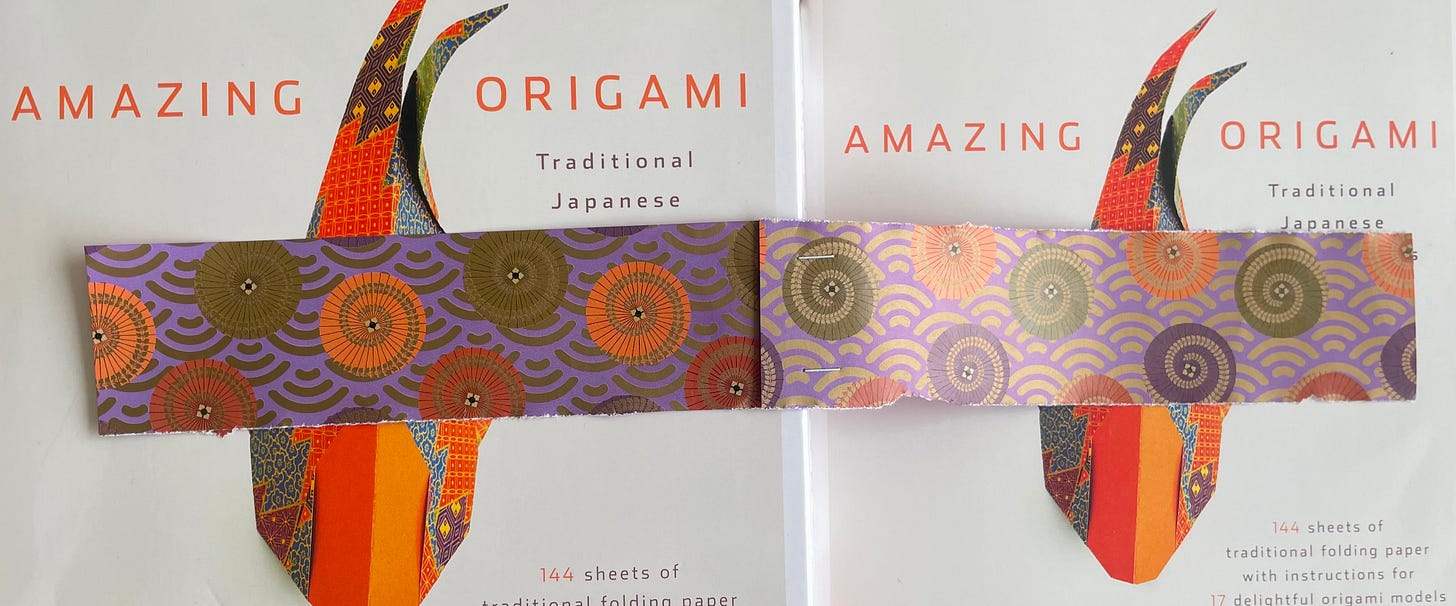

Time is a Mobius Strip (WTF!)

Take a strip of paper.

Make a loop on one end, and stick the ends together. You have a Mobius strip in your hands.

End of Mathematics lesson.

Now indulge me, please. Take a pen and draw a line in the middle of the strip, along its length. As you keep drawing the line, you will notice something strange.

After completing one round, you don’t arrive at the same place you started, but you are upside down, and only halfway through.

What just happened?

If you keep drawing the line, you will need to complete one more round to arrive at the point you started. So two rounds, instead of the one you would expect from a simple ring of paper.

So, how about this

Imagine someone looking at you from outer space using a giant telescope. In the beginning, they see your life journey as a straight line, a linear view of time. Once they zoom out, they realise that your life is circular, because now the curvature of the straight lines starts to appear.

But your life is both at once.

The linear view of time favours the experiencing self. The circular view of time favours the remembering self.

Combine the two, give it the twist that is the human condition or your reality, and you get

Time is a Mobius strip.

We are a combination of our experiencing self and remembering self. Over time, we go through similar events and stories of success, failures, actions and reactions.

We need to go over it twice - The first time through our experiencing self, the second time through our remembering self.

The first round traversing the Mobius strip is our experiencing self, feeling that life is upside down. It’s only the second round, the remembering self, which helps us make sense of it, bringing us back to a baseline.

Without the remembering self, life feels upside down.

But wait, there is one more thing you need to do with the Mobius strip.

Now on each side of the line, write down the words experiencing and remembering.

And cut the strip along the line.

You would be surprised by what happens.

Because instead of two separate Mobius strips, you would get one long Mobius strip! I am not kidding. This is what it looks like

So what does this one long Mobius strip tell us?

You cannot dissociate your Experiencing Self from your Remembering Self. You cannot ask, ‘How was it on the whole?’ without asking, ‘Does it hurt now?’ You cannot suppress the feelings of regret, grief, and guilt because you ARE experiencing them in the moment. You cannot bury these feelings either because your Remembering Self cannot let go of them.

And this brings me to how we could deal with regret, grief and guilt.

Grieving, for the things you lost2

Between 2010 and 2014, the report card of my life looked like this

37 applications. 34.5 rejections. 2 and a half admits. 0 funding.

This was the story of my PhD dreams. For four years, I put myself through two rounds of the GRE, countless SOP drafts, a collection of rejection templates (all of them unfailingly polite) and what should have been a lifetime membership of DHL. I was committed to putting my life on an academic track, pursuing a doctorate in media studies, and aiming to move away from life in the corporate world.

The two-and-a-half admits gave me a lot of hope, the kind that is akin to a flame that flickers for a while before dying out forever. The rejections stung, but what hurt me more was the absence of a path ahead. Instead of my efforts, I started judging myself through my outcomes. Self-funding a social sciences PhD was out of the question, I was not a complete fool even then.

So in the summer of 2014, I buried the PhD dream. I told myself

I am either not good enough for it, or maybe I don’t know how to write applications. Either way, this is the end. (Much later in life, I realised that academia too can be a broken and exploitative setting.)

Thanks to an ongoing education loan and the cost of living in Bombay, I continued down the path of research (consumer research for brands). I walked that path for about fourteen years, and it opened new doors for me. I travelled to Kenya, South Africa, Nepal and Myanmar for work. I got a six-month stint living and working in China, which gave me a whole new perspective of looking at cultures closely. I got created for myself the opportunity to take a three-month sabbatical, where I slow-travelled through Bosnia & Herzegovina, Armenia, Georgia, and the Himalayas.

My remembering self taught me the value of those four years. Writing countless versions of SOPs made me a better writer and researcher. I realised that the foundational principles of research are similar across academia and corporate. And most importantly, those four years of rejection made me introspect. And grieve for the thing I had lost. Failure slaps you in ways success cannot caress you. My confidence and self-image took a hit, but it gave me the gift of self-reflection.

All through it, my love for figuring out ‘Why do we do what we do’ remained. WandaVision did get the ‘What is grief, if not love persevering’ bit right.

Because in these fourteen years, I realised that my love for ‘Why do we do what we do’ returned in another form. Of well-paying corporate work, answering similar questions, for a different master.

And it taught me something important

It is important to sit with your grief. Acknowledge it, embrace it and let it wash over you.

Give it the due time and respect it demands. Do not bury it. Let it fade away with time.

And somewhere along the way, it will become a bittersweet memory. It would become the hometown you migrated from - Too small for your shoes because you have become a different self, and that self does not pine for an imagined past. And yet, too big for your heart, because a part of it still stays with you, like scars that heal with time, and yet leave their marks.

My experiencing self - felt and grieved, and my remembering self - understood.

Regret, for the things you did not do

Through my 20’s and early 30’s, I did not take care of my body. I ate indiscriminately and exercised rarely. I slept poorly and worked relentlessly. The only solace I had was that I never abused tobacco or alcohol, but then the rest of my actions were poor enough that I was physically ageing faster than my chronological age. I developed lower back issues bad enough to warrant a suffocating MRI, and my doctor flat-out asked me to fix my lifestyle.

I did not fix it.

And while I did make minor adjustments, they were ridiculously short of what I needed to do. In my mid-30s, I saw the compounding impact of my poor lifestyle.

I was diagnosed with high blood pressure. My cholesterol levels were elevated.

Coming from a family with a history of diabetes and hypertension, this was terrible news. My doctor again asked me to fix my lifestyle.

The absolute shock of having hypertension at 37 flipped a switch. My experiencing self moped. I felt irritation, frustration and anger. Towards myself. I cursed myself out for being a complete fool. For not doing the right thing, despite knowing better.

I finally decided to get my act together. I cut down on eating out, added sugar and got myself a Yoga teacher. For the last year, I have worked out four times a week, diligently, with my teacher pushing me gently, each time I surrendered to the mat.

I relied (and still rely) on a teacher because my remembering self taught me that I have a very poor intrinsic desire for exercise. I permitted my teacher to put me through a regimen, that favoured consistency and slow change over enthusiasm and bursts of activity. It favoured systems and processes over sheer willpower and motivation.

In six months, I reversed my elevated cholesterol and developed enough core, shoulder and arm strength to do a headstand. My back issues are a thing of the past. Pleased to report that I continue on my Yoga journey (and secretly aim to start a petition towards banning Ashtanga B w/ hold, for violating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, IYKYK).

I would love to say that I have a great relationship with food, but I aim to fix that in 2025.

It taught me that it is important to

Forgive yourself. Instead of beating yourself over the past, instead of punishing yourself with the regret of actions not taken, be kind to your present self.

Accept that you did what you did, and focus on what you can do today. Make regret productive by taking action. This could help you break the cycle of regret.

Guilt, for the things you did

In 2018, I found myself in Nagorno Karabakh, a disputed region between Armenia and Azerbaijan (which found itself in an active conflict situation in 2020). It is controlled by Armenia (and you require a separate visa to visit). I will spare you the bloody history of the region, but as a site of conflict, the regions bordering Azerbaijan have landmines.

One afternoon, in Artsakh, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh, I walked into the office of HALO trust, a non-religious, non-political humanitarian mine clearance organisation, with a staff of over 8500 people across 20 countries and territories. It saves lives and restores communities threatened by landmines and other weapons of war, such as cluster bombs, stockpiles of small arms and improvised explosive devices (IED’s). It has been working in Nagorno Karabakh since 2001.

Through a series of strange and fortuitous events, a couple of days later, I was at an active landmine site, to observe the demining process. I found myself standing in a minefield, close to mortal danger, and yet it felt unreal. It almost seemed banal, the evil that surrounded me. As I was being briefed, I was told that the people who are de-miners are amongst those who had lost someone to a landmine. The job paid well above the average wage in the region, and HALO Trust had no problems filling up their ranks.

A question lingered in my mind: How do you work with and make a living from the very thing that took away a loved one? How do you work with something that could take your own life?

I got the answer from one of the de-miners.

You have to learn to let go. The fear and the guilt will consume you otherwise. You cannot change the past, you sometimes cannot even change the present. But you can let go, and that will set you free.

This was not coming from someone philosophizing in the abstract, but it came from someone who lost many times over in the concrete. Their Experiencing Self felt the pain and grief of a loved one who passed, but their Remembering Self nudged them towards acceptance. Not in the way that life must go on, but in the way that life must go on by letting go of the past.

We’ve talked about dealing with regret, grief and guilt. But how do you action it all together?

Maintain a ‘Wins’ Folder, go back to it regularly

You were appreciated at work in an email that went out to everybody. Screenshot it.

Someone sent you a Whatsapp message thanking you for helping them out. Star it.

You made progress on your goal. Take a picture.

You had a breakthrough with a mental struggle. Make a note of it.

The day you finally let go of the baggage of a past relationship. Record a voice note.

The day you reconnected with an old friend and cleared the air. Screenshot it.

You picked up a hobby and kept at it. Take a picture of the milestone.

Do this as often or as infrequently as you’d like. Maintain all of these in a folder. This is not an exercise in narcissism, but almost one in self-care. It’s a gentle reminder to your demanding self that you are more than what you are feeling in the moment.

It is permitting your Remembering Self to be in the driver’s seat, if only for a few moments.

I have a picture video of me doing a headstand. I have starred WhatsApp messages of people telling me that they loved my writing. I have screenshots of cohort members from The 6% Club telling me that the course changed their lives.

I go back to these regularly, to remind myself, of who I am in totality - A human being more than the sum of my outcomes. You are more than your regret, guilt and grief.

Thank you for reading this far. I am grateful that you gave me 20 minutes of your time. I hope some part of this made you feel heard or helped you feel, think and live better.

I have one last thing to say. I along with a friend run The 6% Club, a content creation program designed for people with full-time jobs. We help you launch your newsletter, podcast or YouTube channel in 45 days. We neither promise virality nor algorithm hacking, but a sustainable, enjoyable way to build a creative outlet for yourself. We have helped 100+ people so far and could help you too.

This piece of text, the story of Adolf Merckle is borrowed from an insightful post, The Many Worlds of Enough

Please note, I speak of grief for ‘things’ lost, and not people. I am not ready to open a chapter of my life about the people I have lost.

Wonderful essay, Utsav. Such lucid writing with so many insights. Loved the way you used the Mobius Strip to explain your thesis. And the sketches are simply brilliant! Superb.

Read it again, Utsav. Very well articulated! And that boat which has sailed and yet not sailed, trying to find the balance mid-waters is beautiful!