Why are we missing awe in our life

and how reclaiming it will help us rediscover joy and wonder

On 22nd November 2024, as we drove through Sangti Valley, in the Eastern Himalayan foothills of Arunachal Pradesh, our car was filled with excitement and palpable tension. My co-travellers were frantically worrying about something alien to the landscape and the home of the Monpas - believed to be the only nomadic tribe in Northeast India. About 7000 feet above sea level, the black-necked crane had migrated from Tibet, into the calmer parts of the swift-moving Dirang River, which flows through Sangti Valley. Evaluated as ‘near threatened’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, these graceful creatures face challenges from hunting to collision with power lines to habitat loss.

Tibetan Buddhists have revered black-necked cranes as a symbol of peace for centuries. Legend has it that previous incarnations of the Dalai Lama were carried from monastery to monastery on the backs of these holy birds.

But that afternoon, the veneration was for a commodity that was becoming rarer by the minute, not just ‘near threatened’, but racing away to extinction.

Coldplay Tickets.

In the last year, artists' concert tickets have become a priceless commodity. Diljit Dosanjh, Dua Lipa, and Cigarettes After Sex all sold out their concerts in minutes. Reactions online ranged from disbelief to frustration to anger, as accusations flew thick and fast about foul play. I am sure you have been part of at least one WhatsApp group where tickets are being resold. But in all of this brouhaha, we forgot to ask a question.

Why this sudden frenzy to attend concerts?

Those who attend these concerts are India’s top 1%, so it’s not about having sudden access to money. It’s not about the newfound fame of these artists either—Coldplay has been belting out hits for years. Neither is it about some misplaced sense of nationalism—apart from Diljit, none of the artists are Indian.

The problem is far more insidious. It’s the hidden loss that is easy to miss. Easy, because your life could go on without it, and you’d not know of the invisible gaping void.

We are desperate to feel awe.

In a world where almost everything is within reach, in a world where nothing truly surprises us anymore, we are craving that feeling of chills running down our spine, of open-mouthed wonder and being a part of something other-worldly.

We want to be a part of something larger than ourselves.

Ask any true fan who attended these concerts, and you’ll hear the words magical, ‘once in a lifetime’, emotionally moving, etc. Many would report tearing up, feeling overwhelmed, and tinged with a mild sense of disbelief that they could be a part of this experience. French sociologist Émile Durkheim termed it Collective Effervescence—the feeling of energy and harmony people experience when they share a purpose.

The desire to see artists you love and admire is not new. It’s the obscene amount of money we are willing to spend (Economists at Bank of Baroda estimate concert spending in Oct-Dec 2024 to be in the range of 1600-2000 crores), the lengths we are willing to go to procure tickets, and the intensity of emotions we feel when we don’t get these tickets, which are startling and even discomforting.

At the heart of the desperate desire to feel awe, is a phenomenon that is all too pervasive.

The Flattening of Wonder.

Our overstimulated, oversaturated and all-knowing selves are losing the ability to experience wonder. Much like addicts, we constantly need higher doses of experiences to feel something we have not experienced before.

Our benchmark to feel wonder is ever-escalating, and for that we pay a price - that we don’t experience wonder anymore.

To understand why we are experiencing the Flattening of Wonder, we take a mathematical detour. Don’t leave, it is something you have always known, since secondary school.

Prime Numbers.

Numbers that are not divisible by any other number, except 1 and themselves.

The Unpredictability of Awe

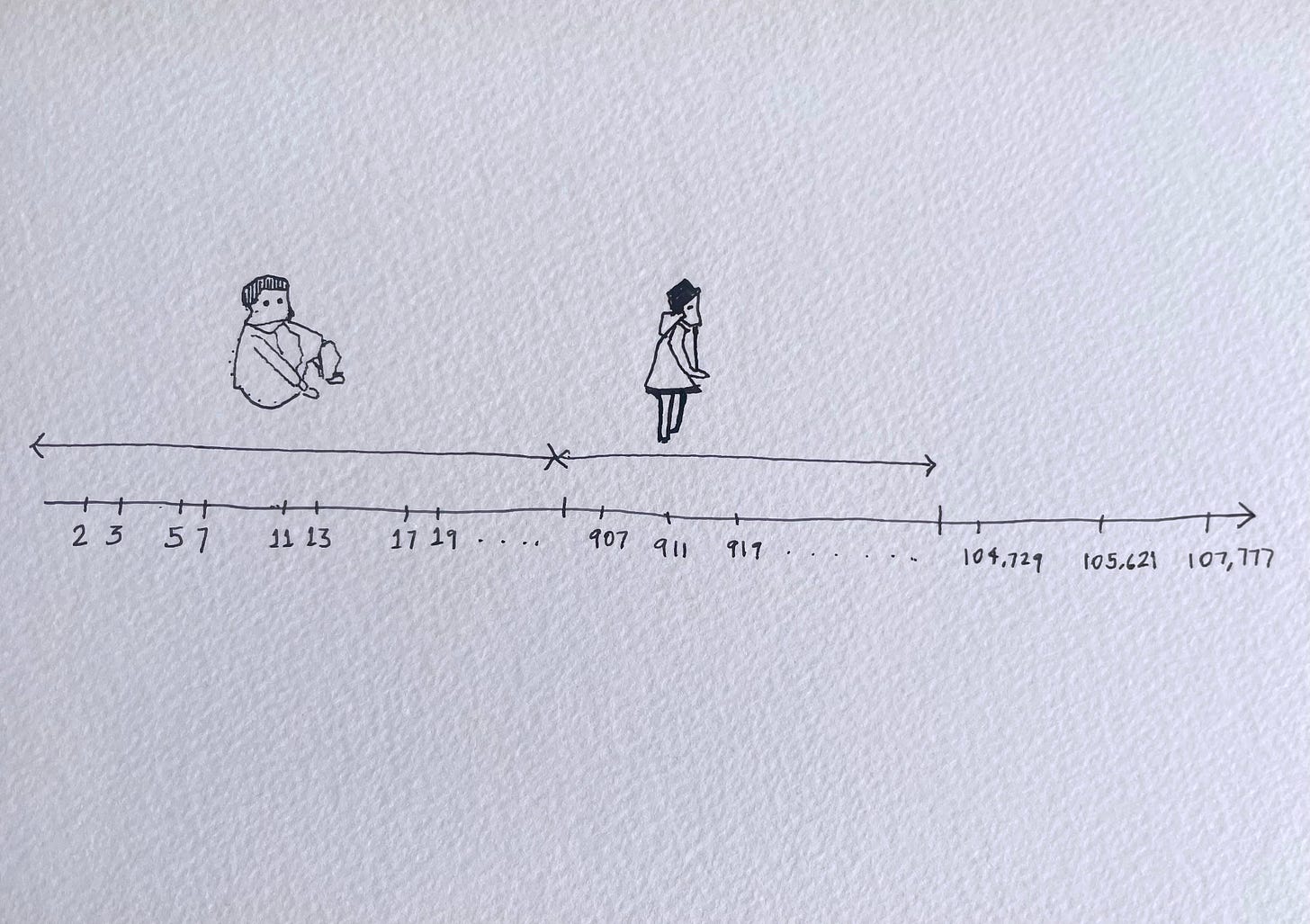

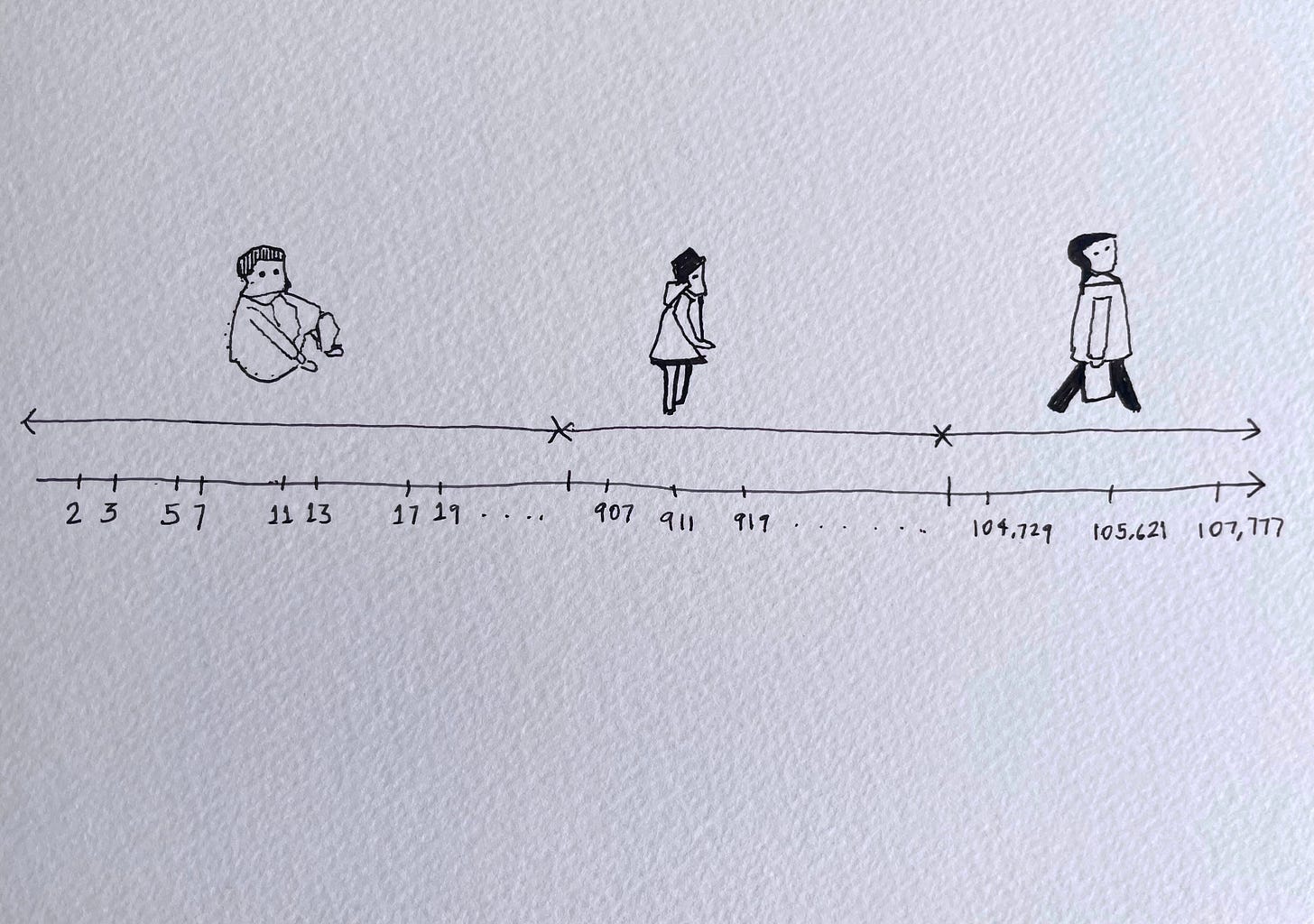

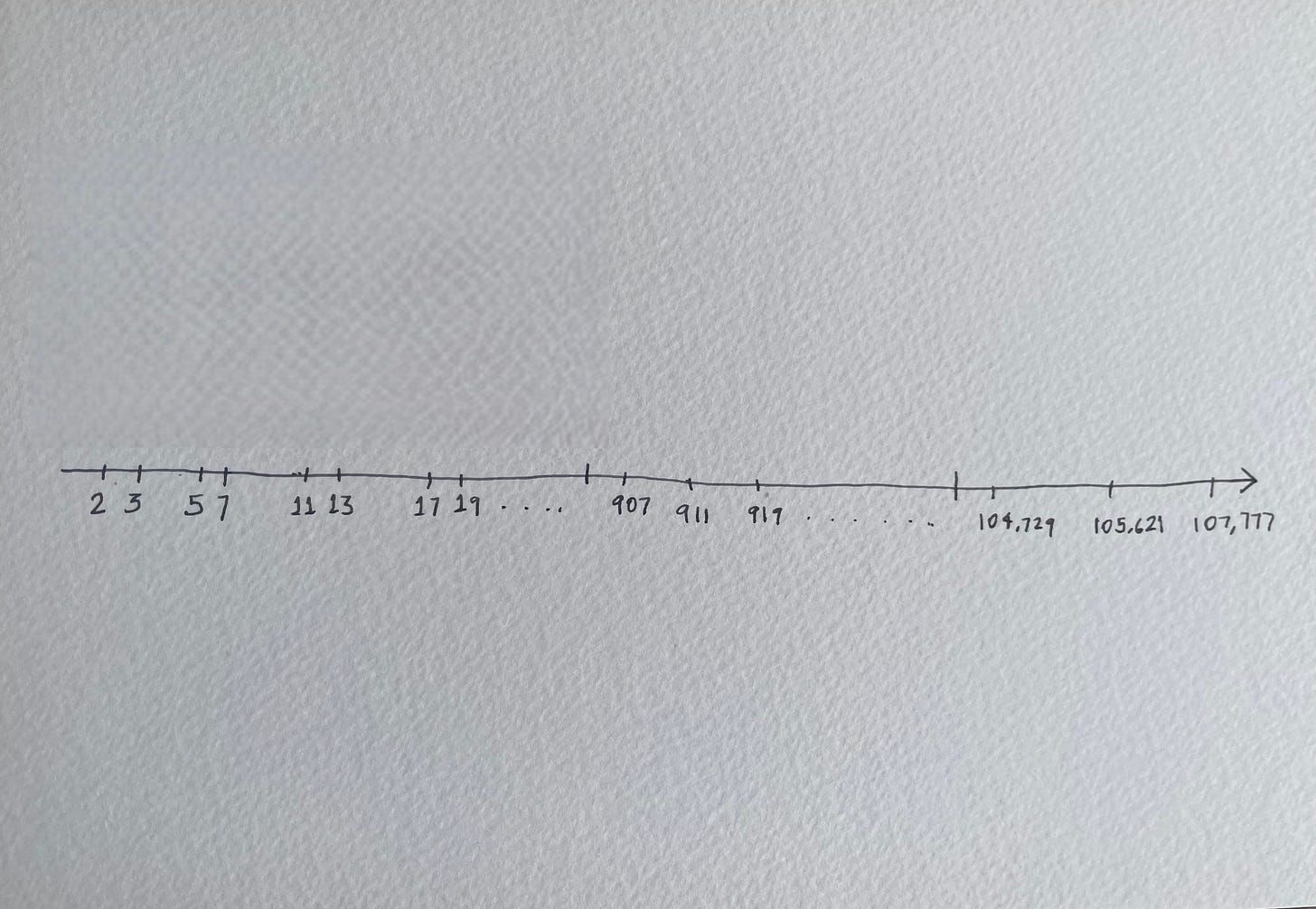

You may remember the ‘number line’. Just a simple straight line in which we would plot numbers starting from 0, conceptually knowing that it would go to infinity. Here is a quick reminder

We all know the prime numbers - 2,3,5,7,11 and so on. As we plot them on the number line and go far enough, we don’t exactly know when the next one will appear. The first few appear quickly, but then they become less and less frequent.

While this may seem like a trivial observation to us, this is one of the most difficult problems in mathematics. There is serious money involved (as solving it would lead to a breakthrough in proving the Reimann Hypothesis, probably the most important problem in pure mathematics) - You can net a cool 1 million dollars for solving one of the seven Millennium Prize problems.

But none of us are solving that problem, so let’s get back to primes.

Now imagine your little self, crawling on all fours, sampling with your lips anything you could lay your hands on. Everything is new and wonderful. The ball that rolls on the floor, the stopper of the door, rolling in your pee, the power sockets that fit your fingers so well etc. And if you end up wandering outside the house, the mud tastes yummy! You approach everything with new eyes and use every sense of yours to explore the world. You are in awe of everything.

Now imagine crawling on the number line. And think of each prime number as something to be in awe of.

You will encounter so much awe (25% of numbers up to 100 are prime numbers).

As you grow up, you understand the basic nature of objects and things around you. The ball is no longer as fascinating, neither is the door stopper. Your parents don’t need to child-proof the house anymore, since you are not likely to stick your fingers in the socket. And the nature of your questions change

What is money and why do we need it?

If fossils are all that is left of dinosaurs, how do we know their skin colour?

Where did Nanaji (maternal grandfather) go and what is death?

The answers to these questions either confuse you, intrigue you or open completely new worlds. Not everything fascinates you, but on the prime number line called life, there is enough to keep your curiosity buzzing.

A few years go by, and now you are the adult who is in control of your life (hehe). You know your way around a career, money, and relationships and have mastered the timing of when your water heater needs servicing (hehe ok I will stop). As you walk along the prime number line, not much makes you gasp with wonder. Each point on this line seems farther away than the other. Standing at one, the other seems out of sight. The horizon is empty, and unlike your younger days, the possibility of finding wonder seems bleak. There is too much happening in life anyway, and you are so tired all the time. There is simply no time for wonder.

Rachel Carson, one of the pioneers of the global environmental movement, said it best

A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood.

If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantment of later years … the alienation from the sources of our strength.

As you go through life, this is how the graph of wonder looks like

Prime numbers and wonder are inherently hard to predict. We don’t know when wonder and awe would smack us in the face and leave our mouths agape. And while prime numbers and wonder are infinite, our time on this earth is finite. This reality presents a problem made trickier by how we have distorted both time and space.

Humour me please, I assure you that this is not a crash course in physics, the nature of time or philosophy.

This is a crash course on how to find prime numbers in life.

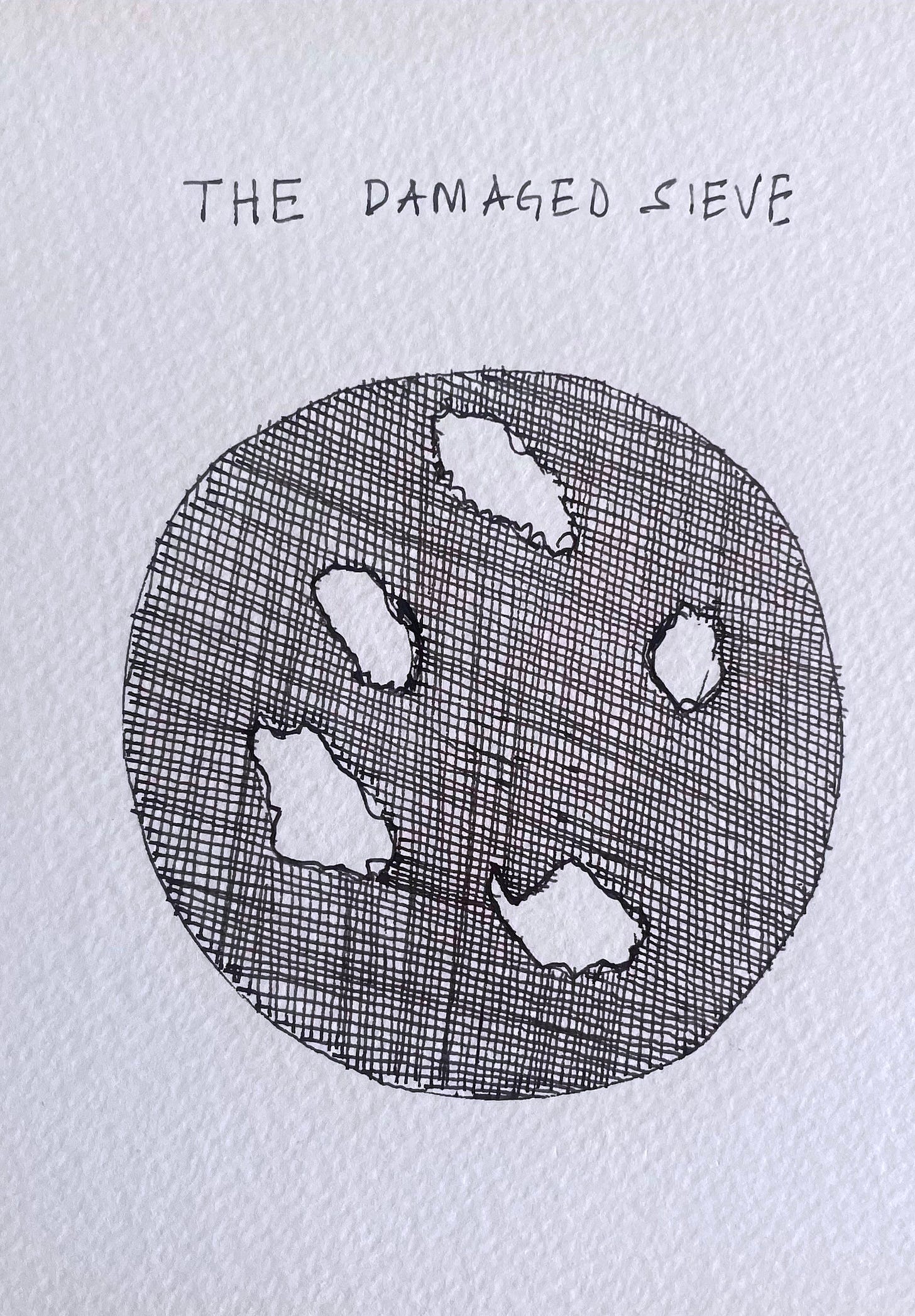

The Clogged Sieve of Experiences

As mathematicians try to solve the prime number conundrum, they use the concept of a sieve. Simply put, imagine you are putting all numbers through a sieve, and you want to strain out only prime numbers.

Now instead of numbers, let’s put everything we encounter in life through a sieve, aiming for it to only strain out wonder and awe on the other side. Ideally, it should work well, but we have a problem - The sieve is becoming clogged.

With what?

The sheer number of things we are trying to put through a sieve.

We have accelerated the pace of life - Money allows us to buy more things that we can realistically use, and then whatever we get, we don’t enjoy it for too long. We normalize it quickly. It’s called the Law of Hedonic Adaptation.

When it comes to experiences, we are limited by time. But thanks to social media, we can vicariously travel, and experience the most beautiful of sights and the rarest of experiences on our screens, before swiping to the next one. You can see with as much ease the Aurora Borealis as you can spot the elusive snow leopard in Ladakh.

By accelerating both time and pace, we are asking ourselves to experience too much, too fast.

As the sieve becomes clogged with the banality of mindless goods and incomplete experiences, we feel fewer and fewer things of wonder.

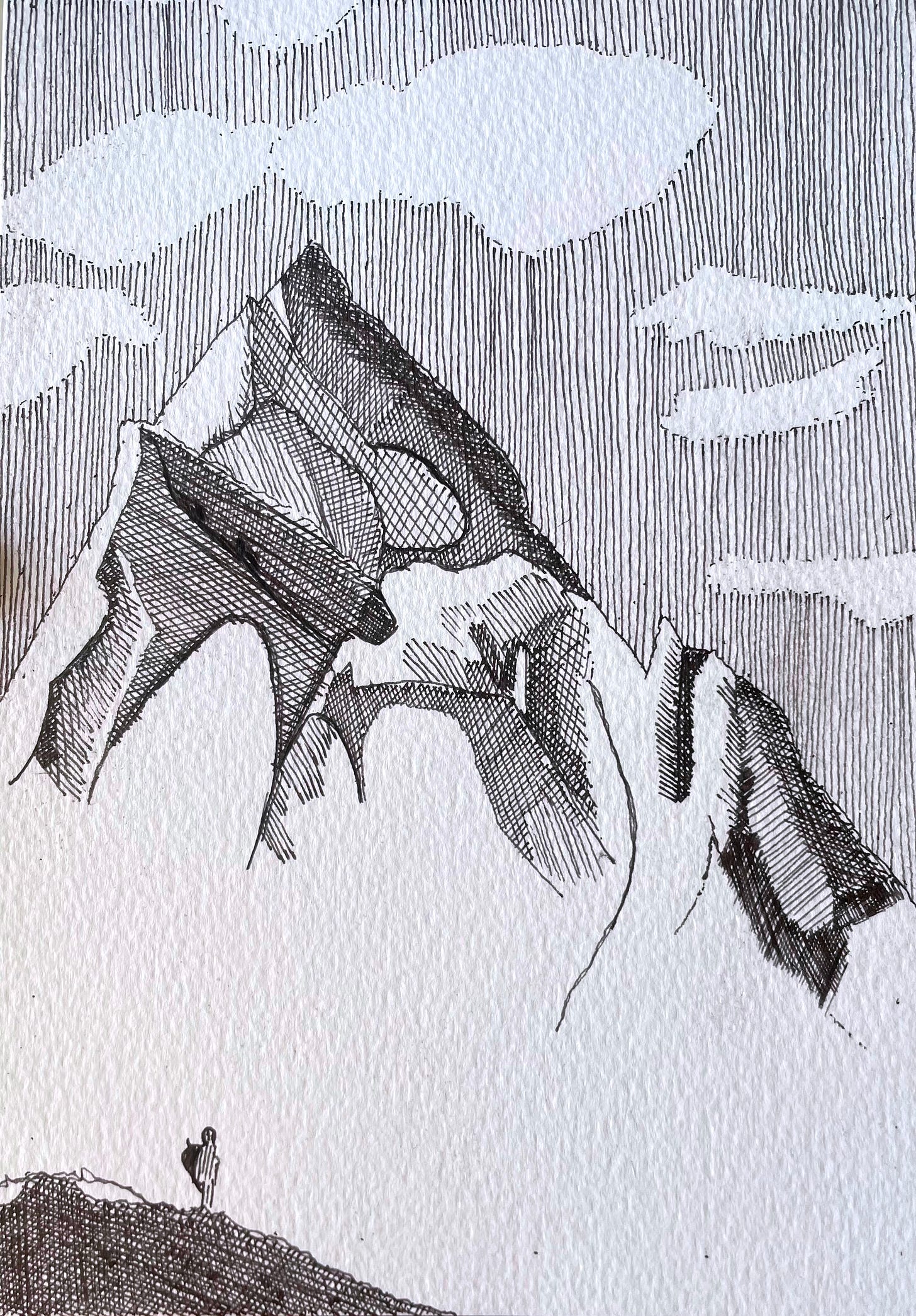

Consider one of the most obvious ways to experience wonder and awe - Travel.

I know a thing or two about it. I run a travel, culture and history podcast Postcards from Nowhere, a global top 2% podcast exploring the strange, obscure and fascinating things around the world - one ten-minute episode at a time.

In the 5+ years I’ve run the podcast, I have come to realise something - that the nature of travel has changed for the worse.

As we travel, we mostly hit the highlights in each place. We want to feel awe when we see these highlights. We want to imprint that feeling in our memory. We feel that taking a photograph will do that - but it rarely does. John Ruskin, a polymath of the Victorian era said of the modern tourist

Rather than using photography as a supplement to active, conscious seeing, they use it as an alternative, paying less attention to the world than they have done previously from a faith that photography automatically assured them possession of it.

Even if we do feel awe, it’s so fleeting that before it can take our breath away, we are breathless to get to the next ‘awesome’ experience. That 12:10 pm metro that you need to catch ain’t waiting for you.

And neither is awe.

In the year 1862, Thomas Cook became the first company to offer to see Europe by train in a week. This was revolutionary because it was impossible till then to traverse the continent at such breakneck speed. John Ruskin was not impressed

No changing of place at a hundred miles an hour will make us one whit stronger, happier or wiser. There was always more in the world than men could see, walked they ever so slowly, they will see it no better for going fast. The really precious things are thought and sight, not pace. It does a bullet no good to go fast, and a man, no harm to go slow, for his glory is not all in going, but in being.

It is in this being, that we experience awe.

But since our sieve is now clogged, we find a different way to experience awe.

We prefer to chase rare, elusive and expensive experiences, which crash into our sieve. The experience does produce awe, but it also damages the sieve, making it harder for us to be awed by the next experience.

But wait, we have not answered a basic question - Why care to be in awe at all?

In a nuanced study from Japan, one group of participants watched videos of awe-inducing nature (footage of mountains, ravines, skies, and animals from BBC’s Planet Earth). Other participants viewed more threat-filled awe videos of tornados, volcanoes, lightning, and violent storms. The finding suggested that

When we experience awe, regions of the brain that are associated with the excesses of ego, including self-criticism, anxiety and even depression quieten down.

Wonder, the mental state of openness, questioning, curiosity and embracing mystery, arises out of the experience of awe.

So if travel ain’t cutting it, rare experiences are blowing too much of a hole in our pockets and our sieve, how should we experience awe in everyday life?

Here are 3 ways to do it

Go Deep

In June of 1993, at a mathematics conference in Cambridge, England, Andrew Wiles gave a series of lectures cryptically titled “Modular Forms, Elliptic Curves, and Galois Representations”.

No, you don’t need to understand it (and neither do I).

His argument was long and technical. Finally, 20 minutes into the third talk, he came to the end. Then, to punctuate the result, he added:

“Implies Fermat’s Last Theorem.”

To an outsider like you and me, the world of mathematics is an image of a boring drab world of professors in tweed coats obsessing over Japanese Hagomoro chalk and the merits of linear algebra. We are far more attracted to the world of cinema, politics and business where one can find stories of historic wins and colossal downfalls, of sheer grit, ingenuity and a truckload of risk. The world of science (outside of the annual Nobel Prize announcement) is timid by comparison, for there are no heroes in the present, and rarely any in the past.

That was about to change. The announcement electrified his audience—and the world. The story appeared the next day on the front page of The New York Times. Gap, the clothing retailer, asked him to model a new line of jeans, though he demurred. People Weekly named him one of “The 25 Most Intriguing People of the Year,” along with Princess Diana, Michael Jackson, and Bill Clinton.

But why?

Because for 350 years, Fermat’s Last Theorem had remained unproven. And I assure you, unlike the name of his lecture, the theorem is deceptively simple to understand.

Do you remember Pythagoras’ theorem? Right-angled triangles, the height of buildings question and all that?

Pierre De Fermat was a French mathematician who asked a natural next question: Can you find a similar set of numbers in higher powers? In other words, are there numbers that solve the equation

.. and so on. He wrote in the margin of his notebook, that, NO, no solution is possible.

Andrew Wiles first encountered this at the age of 10, and like any kid who was obsessed with mathematics, he fantasized about solving it. Everyone including his PhD advisor asked him to stay away from the problem - it was unsolvable and would be a waste of Wiles’s time.

Wiles had other ideas.

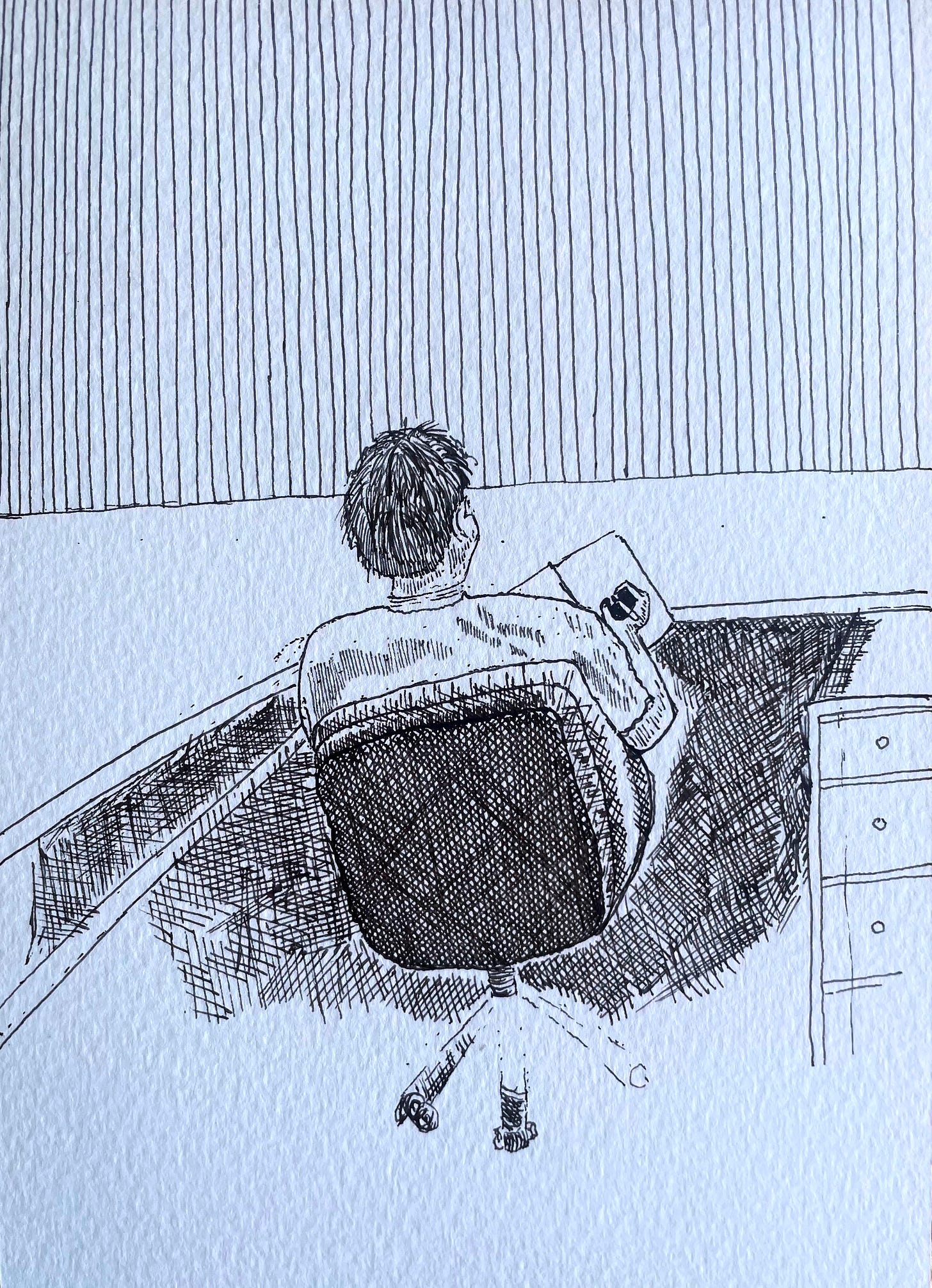

Later, as a professor of mathematics at Princeton. he worked on the problem. Alone and in secret in the attic of his home - for seven years. He went deep into it.

He eventually found it.

And almost as soon as he announced the proof, it had logical flaws. Seven years of deep work was about to be undone. There was no QED.

From June 1993 to September 1994, he worked tirelessly with a small set of mathematicians to fix the proof. He made some progress, but the mathematical community was getting impatient. They wanted to examine the proof and see if they could fix it (and get a shot at fame).

On the verge of admitting defeat, Wiles took “one last look” at his original approach to try to see precisely where he had gone wrong. In the BBC documentary The Proof, he describes what happened next. “Suddenly, totally unexpectedly, I had this incredible revelation.” There, “out of the ashes” of his failed technique, appeared the very tools he needed to prove it. He said

It was so indescribably beautiful, it was so simple and so elegant. The first night I went back home and slept on it. I checked through it again the next morning, and I went down and told my wife, ‘I’ve got it! I think I’ve found it !’.

And it was so unexpected that she thought I was talking about a children’s toy or something, and she said, ‘Got what?’ I said, ‘I’ve fixed my proof. I’ve got it.1

In May 1995, in two papers in the journal Annals of Mathematics. The final proof, and its accompanying discussions, ran 130 pages.2

Wiles had done the impossible.

He could do it only because he decided to go deep. He committed his time and energy to the problem and tried multiple approaches. 350 years of attempts could not do what Wiles did.

But there is another part of this story that is as important as the proof itself.

The 350 years of attempts.

Across centuries, multiple mathematicians have attempted to find the proof. Some of them made progress, such as the two young researchers from the University of Tokyo, who came up with the Taniyama-Shimura Conjecture, an important step in the proof.

However, the true beauty of this story lies in the fact that, in an attempt to prove the theorem, mathematicians took unconventional paths and made sweeping contributions to other areas of the subject.

The attempt to prove Fermat's Last Theorem spurred significant advances in algebraic geometry, number theory, modular forms, elliptic curves, representation theory, and even computational mathematics.

And with it, gave us an advancement that we could apply to our own life

Going deep into any field/subject allows us to go vast.

We are trained to think that going deep, spending too much time in one area, would lead us to have narrow ideas and limited knowledge.

But the world is more complex and interconnected than we understand.

To go deep, we must understand a field's fundamental nature, which necessitates finding bridges to other fields.

Find something that interests you, and go deep into it. Explore rabbit holes at will, and give yourself permission to be lost in them. Spend your energy, time and even money on exploring this interest.

Do this with some degree of regularity. Sacrifice some pointless doom-scrolling and say to yourself “I like this, and I am going to do more of this.”

For me, the process of writing this Substack is the act of going deep. I have been writing every week for the last five years (for my podcast). My desire to write more reflective pieces led me to make sketching an integral part of it. In my desire to be a better writer, I crossed the bridge from words to visuals and found that the pen that writes can also be the pen that sketches. The pen always had the quality, but it was me who needed to go deep and discover it.

Going deep into things will uncover a second order of awe - of how depth will unlock vastness and epiphanies. In the jaded reality of urban living, where the linearity of our capitalistic lives strips joy, find yourself dancing on the number line, waltzing your way to discover new, hitherto unknown prime numbers.

Spend Time in Nature

In 1749, the philosopher Rousseau was on his way to visit his friend, Denis Diderot, who was serving time in a prison on the outskirts of Paris. As he walked through the rolling hills, he mulled over this question.

“Has the progress of sciences and arts done more to corrupt morals or improve them?”

Rousseau was living in Europe which was going through The Age of Enlightenment. The Enlightenment featured a range of social ideas centred on the value of knowledge learned by way of rationalism and empiricism. And he was wondering where it was taking the world.

Contemplating that question, he was knocked to the ground. He went into a trance state and had an epiphany - That the Age of Enlightenment, of science, industrialisation, formal education and expanding markets, was a lie. It was destroying the soul of humanity. It was a companion of the systems of slavery and colonization and a cause and rationalisation of economic inequality. It was decimating the forests of Europe, polluting its skies and filling its streets with filth.

He strongly felt that in our natural state, we are endowed with passions that guide us to truth, equality, justice and the reduction of suffering - our moral compass. We sense these intuitions in music, art and above all, being in nature.

In that experience outdoors in the hills outside of Paris, Romanticism was born. A movement that advocated for the importance of subjectivity, imagination, and appreciation of nature in society and culture. Passion, intuition, direct perception and experience were privileged over reductionistic reason.

Romanticism believed that natural processes - thunder, storms, winds, mountains, skies, life cycles of flora and fauna - have a spiritual meaning and that is where we find the sublime.

This spirit of Romanticism inspired Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein and stirred the poetry of Coleridge, PB Shelly and Wordsworth. It led to the epic voyages of James Cook, Alexander von Humboldt and eventually Charles Darwin.

A couple of centuries later, Rachel Carson noted

Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary in life.

On a cold morning in December 2024, I found myself on a nature journalling and tree walk in Cubbon Park, the green lung of Bangalore. I have always enjoyed my time here, as it serves as a welcome break from the world of startups and traffic jams. I remember it being the place where our group of friends reconnected in person after the first wave of the pandemic ended and physical spaces became accessible again.

But I had never slowed down and stopped to notice nature more closely. The instructor asked us to pick up anything from the ground that intrigued us, and I picked up a half-decaying leaf of a peepal tree. As you’d see in the image below, not only did it take me back to a cherished childhood memory, it allowed me to marvel at the complex set of veins in the leaf.

The more closely I observed it, to understand its essential nature and then sketch it, I realised I had an impossible task at hand.

The webbing of the veins was so complex, that in no way could I replicate its design on paper. The instructor asked me to ditch my fountain pen and pick up a water brush. She picked up the colour palette, mixed yellow and green, and with a few simple strokes, brought alive this sketch of a half-dead leaf. The watercolour complemented the venation I had done with my fountain pen, and it opened a new door for me as a beginner artist to experience a new medium. My transformation was dual - This commonplace but intricate leaf design (reticulate venation) put me in a state of awe - and allowed me to experience first-hand a new (to me) technique in art.

I wondered, how many such marvels of nature, accessible in everyday experiences are available to me. And how many things could they inspire, just the way I discovered the joys of watercolour bringing to life a half-dead leaf.

If you, like me live in the city, make time regularly in your life to not just be in nature, but also observe and engage with it closely. You can attempt any of the following

Download the Merlin Bird ID app, fire it up and identify the calls of different birds. And you will know which bird is calling the next time you encounter it.

Go online (or even better, to a local bookstore) and find a book about trees in your city. Take them to a nearby park/forest and see how many trees could you identify. If you prefer a more digital approach, download the Seek app, and use it instead.

Pick up anything lying on the forest floor, and look at it for 2-3 minutes. Notice what stands out for you. Pay attention to what you pay attention to. And ask yourself “Why do I find this fascinating?”

Sit down, and sketch or paint, no matter how well or how poorly, whatever catches your fancy.

Let the damaged sieve of awe be repaired by half-dead leaves, lying in plain sight. Let it be repaired by sweet birdsong, enveloping you in serenity.

I assure you, that you’ll come away with a richer appreciation and understanding of nature, and dare I say, yourself.

Find Moral Beauty

In January 2014, 15-year-old Aitzaz Hasan sacrificed his life to save hundreds (maybe even thousands) of students from a suicide bomber. His home city of Hangu is no stranger to sectarian violence and has a long history of repeated attacks on the Shia population.

Aitzaz went to school in Ibrahimzai, a Shia-dominated region in northwestern Pakistan. He and his two friends were running late for school when Aitzaz noticed a suspicious man standing near the school. Despite his friends telling him not to go, Aitzaz went to confront the man and discovered that he was wearing an explosive vest. The man made his way towards the school but Aitzaz, at first threw a stone at him but missed. Aitzaz chased him, and bear-hugged him down, prompting the man to detonate the bomb, killing both of them. Nobody else was harmed.3

The first time I came across the story of Aitzaz, I remember getting goosebumps. For I could not imagine the kind of moral courage this young boy must have had. And how lacking I found myself in it.

A purity of goodness and action marks exceptional virtue, character and ability. The courage of other people, their kindness, their strength and their ability to overcome odds move us in fundamentally human ways - and generate awe.

Be it your social media feeds or WhatsApp groups, find spaces where you are more likely to discover stories of moral beauty.

In your life, find people who demonstrate such qualities, and you will find yourself gravitating towards them, even wanting to be like them.

As the sieve of awe tatters away under the burden of accelerated time and the pace of urban living, renewing it would require us to slow down. It would require us to consciously seek ways to go deep, spend time in nature and find moral beauty. In your own life, you may not have the ability to do all three, but even if you could give space to any one of them, you would realise

That within you is all the awe you need. And like prime numbers, there is infinite awe to experience.

Thank you for reading this far. I am grateful that you gave me 20 minutes of your time. I hope some part of this made you feel heard or helped you feel, think and live better.

I have one last thing to say. I along with a friend run The 6% Club, a content creation program designed for people with full-time jobs. We help you launch your newsletter, podcast or YouTube channel in 45 days. We neither promise virality nor algorithm hacking, but a sustainable, enjoyable way to build a creative outlet for yourself. We have helped 100+ people so far and could help you too.

My writing does not do justice to how moved, and speechless Andrew Wiles gets when he talks about it. Please see it here from minute 44:00 onwards

This story has been sourced from the Nautilus piece, How Math’s Most Famous Proof Nearly Broke

This story has been sourced from the Brown History Instagram page

I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading this piece. It spoke to everything I have been feeling in wanting to change in order to live more wholly. So beautifully written too.

Bruh🫠👏👏👏

Being a 19 year old who is more sort of renaissance person into nature love and beauty in nature and mundane things and also being simultaneously deeply delved into mysteries of sciences from Navier Stokes Equations to the worlds of Quantum Physics, this post kind of gave me such a fantastic grounding❤️

I cannot explain to you in words of how deeply people like yourself inspire me to not give up on myself to become a polymath one day!

Just realised you write, run a podcast , and draw?!

Jeez that's one hell of a combination and I cannot express in words how deeply this post has impacted me!!

This is a perfect masterclass on writing a mindblowing newsletter as well✨🫡

Believe me I did not for one moment feel like quitting it ,unlike my attention deficit brain😂

Maybe I definitely need to meet you once in Banglore, maybe sometime!

(If you read this rant don't think otherwise of me I love ranting hehe)

Tldr: loved it, excited to meet you irl soon!

With awe and inspiration,

Aryan ❤️✨