How to live an intellectually rich life

.. and how living one is easier than you think

Go to the main page of Wikipedia.

Click any link that leads to a Wikipedia entry. For that page, click the first hyperlinked word in the main text. Keep doing it - Your journey will look something like this.

Now, try this for several pages. Make them as varied as Nuclear Gandhi, Cow Tipping, and Exploding Trousers.

All of them will lead you to the Wikipedia entry on Philosophy.

In 2017, three mathematicians from the University of Vermont published a paper titled Connecting Every Bit of Knowledge: The Structure of Wikipedia’s First Link Network. They tested this hypothesis over a dataset of 4.7 million English Wikipedia articles and found that philosophy was the page where the highest no. of articles ended.

95% of all Wikipedia articles led to philosophy.

What is the point of this?

Imagine you are sitting in a meeting at work. The discussion is around the plan your team had set in motion last quarter, and the results are being reviewed. Data is being twisted and harassed to confess to whatever version of reality the group wants to see. You are sitting there, and you see through the charade.

You’re wondering what the point of this is? You did not slog through life, battling inhuman entrance examinations, irrational parental expectations and eight rounds of interviews to get this coveted job, only to do this data jugglery. You’re wondering - why is nobody asking the fundamental, first principles questions? Why are we not questioning our premise? Why are we misinterpreting cause and effect? Why are we chasing these vanity metrics, when the metrics themselves are poor indicators of reality? Why have we accepted as gospel truth some ‘self-evident’ principles?

The meeting is adjourned, congratulatory messages are passed around, and a vague way forward is discussed. You shake your head, sigh deeply and groan internally, grab coffee and head to the next meeting.

You, my friend, are going through Epistemic Anxiety.

Anxiety is an emotional response to risk. When we experience anxiety about an event, we perceive the risk to be real and possible, likely to occur in the near term.

Epistemic Anxiety is the feeling of uneasiness, tension, and concern when you want to know the truth. You worry that your knowledge is incomplete and full of errors, and you may believe it.

You either lack the resources, methods or agency to get to the truth.

The reason why Epistemic anxiety bothers you so much is because it is at odds with a universal human feeling: An innate desire for truth.

In a world of information overload, our epistemic anxiety is off the charts. We are constantly bombarded with so much information and misinformation, that our brains are losing the ability to sift through it.

We are no longer able to parse the information we see, and thus, we default to our biases. We are aware of this, and that is why we want to live a life in which we can reduce this anxiety.

But the way to the ‘truth’ is a journey filled with complications, rife with uncertainty and overflowing with pitfalls.

If we were to embark on an intellectual journey that would lead us to this ‘truth’ and allow us to reduce epistemic anxiety, we would need to immerse ourselves in the world of ideas, those that are novel and beyond our current comprehension.

But before we get onto this journey, we need to take another one. Back in time to the year 1970, at the University of Cambridge.

The Game of Life

John Conway was an English mathematician, who resembled a young Jack Nicholson from the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Apart from making contributions to the theory of finite groups, number theory, and combinatorial game theory, he was also known for growing a branch of mathematics called recreational mathematics.

Simply put, math done for entertainment (gasp!)

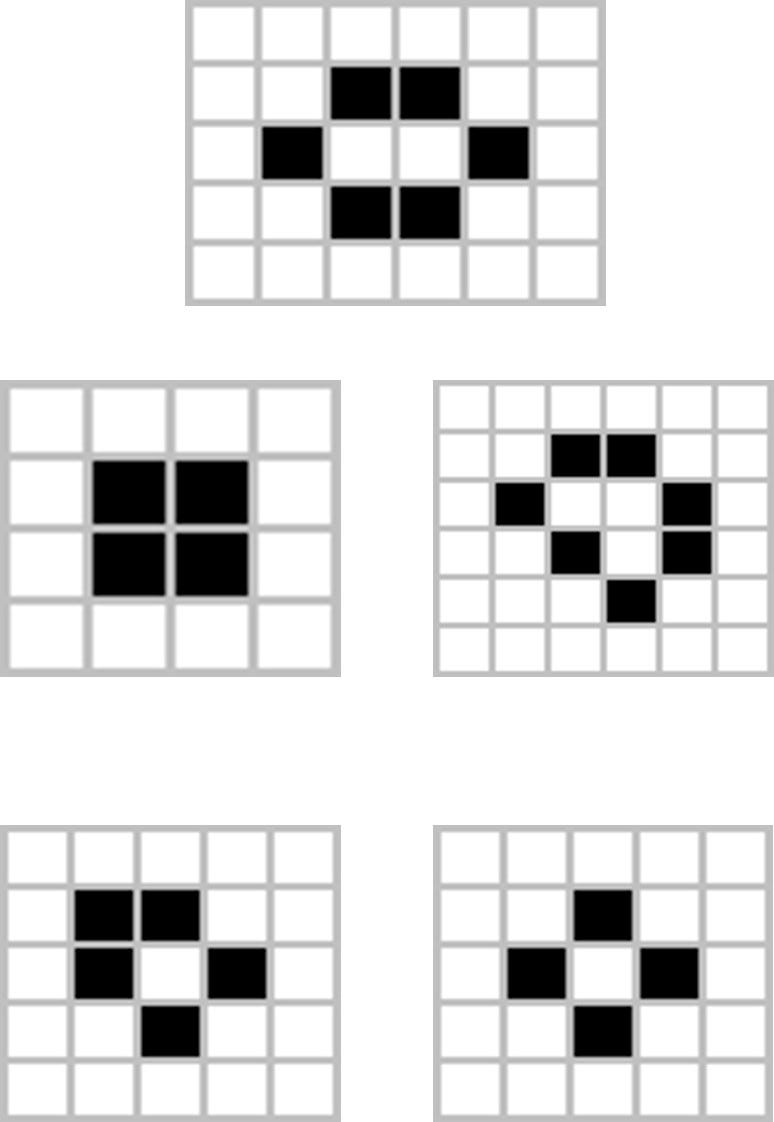

In 1970, he invented a game called Conway’s Game of Life, which you and I are going to play. Don’t worry, it’s merely recreational mathematics.

The fun begins with the fact that it is a zero-player game.

Eh, what? What kind of game has no players?

It’s a game where the starting point defines the outcome. And it is governed by rules.

Do you remember the first time you got your hands on a computer, probably in the school computer lab, where for some inexplicable reason, one had to take off shoes to enter?

One of the games you may have played was Minesweeper. A large grid with mines hidden in each cell, and you had to click in such a way that you did not trigger any mines.

Imagine a similar kind of grid. And instead of clicking, you define the starting point, saying how many of these cells are filled.

You can have as many or as few cells as you’d like. The game moves forward with the following rules

Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies, as if by underpopulation.

Any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on to the next generation.

Any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies, as if by overpopulation.

Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell, as if by reproduction.

You can play the game here. And if you play it long enough, with varying types and numbers of cells as starting points, something strange will happen.

I urge you to not skip the video, as it is central to the understanding of this piece.

What the f*ck did you just see? The Game of Life set to the haunting title track of the psychological drama film Requiem for a Dream!

Now imagine if each of these darkened cells were ideas.

So what happens when you have just a few ideas? What happens if you have a few more?

Most of them die.

Even with enough cells, a pattern quickly emerges.

By surrounding ourselves with too few ideas, we let our ideas die. Our ideas become Still Lifes.

By surrounding ourselves with too many ideas of the same kind, we just recycle through the same ideas. Our ideas become Oscillators

Our ideas need to be diverse. Our ideas need to be abundant.

This is not a theoretical argument.

Conway’s Game of Life is an example of emergence and self-organisation.

When we surround ourselves with abundant, diverse ideas, complex ideas emerge. These ideas are unique and do not resemble the ideas from which they emerged.

Even if the initial set of ideas seem simple and disconnected, spontaneous order can emerge, leading to brilliant ideas.Emergence and self-organisation are all around us. In the sciences, society, art and in nature.

Ok, but how to have novel ideas? In a life defined by the rhythms of work, relationships and traffic, how does one find the space to discover novel ideas consistently?

Arriving in Vielmere - Home of the Luminspire

To understand this, we embark upon a journey, to the town of Vielmere. Located in a parallel universe and your reality at the same time, you drop anchor on its shore. Only to discover that this ain’t the most hospitable of towns. The locals are not necessarily welcoming, and they look tired. Their faces look ashen, their eyes red with resignation, and their shoulders droop. They spend their nights in town, but during the day, they are nowhere to be found.

You, on the other hand, are looking to scale Luminspire - The Mountains of Knowledge. Legend has it that the most learned of women and men reside high into the mountains. Shrouded in mist, choosing to live silently, these people pursue their field of knowledge assiduously. They rarely ever venture into town, and even if they do, most people ignore them, just as they ignored you.

You can see these mountains from town, but everyone tells you that to get there, you will need to navigate Moradoom - The Evergreen Forest of Late Stage Capitalism. That is where they spend their days.

Navigating Moradoom - The Evergreen Forest of Late Stage Capitalism

Moradoom was once a deciduous woodland forest. About 50 years ago, it was recolonised with a different species of trees - evergreen pine, spruce, fir and oak. In their original form, they used to be truly deciduous - changing with the seasons. Trees, shrubs and herbaceous perennials would lose all their leaves for a part of the year. This fall of leaves was governed by a combination of daylight and air temperatures. Many deciduous plants flowered during the period when they were leafless, as it increased the effectiveness of pollination. The absence of leaves improved wind transmission of pollen for wind-pollinated plants, and increased the visibility of the flowers to insects in insect-pollinated plants.

Unfortunately, the evergreen trees which colonised Moradoom had mixed effects. There emerged two types of trees

Nurturing Deciduous Trees: The kind which provide fruit on alternate years, shade all around the year and firewood towards the end of their lives. They are canopy shy, grow slowly, and left to themselves, would live long healthy lives, providing for both man and animal.

Swallowing Evergreen Trees: These trees grow to gigantic sizes, far surpassing the North American Redwoods. They provide fruit all the time, but seldom provide shade. They grow quickly, are a perennial source of firewood, and grow so closely together that their canopies merge into each other. Thus, they block sunlight so effectively, that the entire forest is engulfed in darkness. They intensify the competition for sunlight, water and nutrients, thereby depriving nurturing trees of the resources they need. They accelerate the spread of disease, thereby leading to the demise of smaller ground-loving vegetation such as shrubs and grasses.

And they swallow entire human lives - physically and emotionally.

The nature of our work feels like navigating Moradoom. The swallowing trees are so high that we cannot climb them, and thus we cannot get sunlight. They are so densely packed together that trying to squeeze past them only means falling, hurting and bruising ourselves.

In the process of feeding these trees, we sacrifice our mind and body. They are relentless in their asks - They always want more, and each time we give more, we are marked as someone from whom more can be extracted.

The cost of their evergreen fruit is paid through the ever increasingly exploitation of our leisure time. We nurture these trees with tears of our dead dreams and the graves of our relationships.

And the only fruit you get is the one that falls on the ground, a consolation disguised as reward.

Getting stuck in Moradoom is easy. In all likelihood, if you’ve read this far, you and I are both stuck in it. It often takes us decades to emerge out of it, but by then we have lost our best years chasing the consolatory fruit. Each day we spend time in Moradoom, and return to our homes at night. What should be a refuge from the tyranny of the forest becomes the cage. We pay increasingly higher emotional and monetary costs to maintain these cages - our rents are always going up, the EMIs never seem to end and there is always something to fix in the house. Whatever is left, we burn it in the meaningless cycle of upgrading - Things we buy to impress people who don’t care about us. Or worse, to impress yourself.

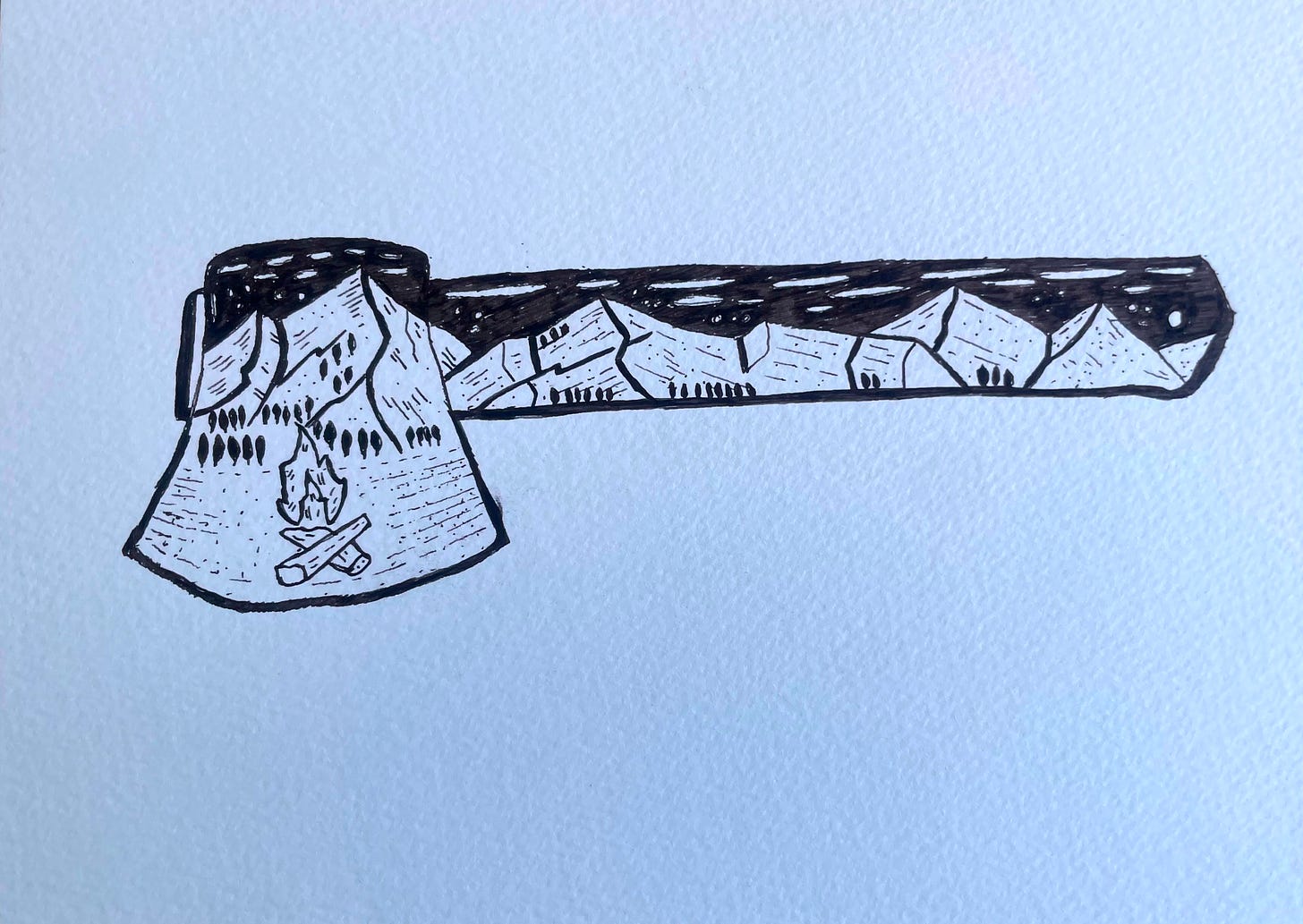

But there is a way to escape Moradoom, there is a way to find more nurturing deciduous trees, there is a way to cut down the swallowing evergreen trees

The Axe of Satisfaction.

In August 2018, in the last month of my three-month sabbatical, I arrived at the Hamta village in Himachal Pradesh. I rented a one-room cottage, and my caretakers were Dolma Aunty and Kalzang Uncle, a couple well into their 70’s. And while a handful of tourists like me came and went, their constant companion was their mountain dog Rambo, who unfortunately lost his eyesight to snow-blindness. Uncle and Aunty used to cook for me, and they also became my companions.

Dolma Aunty and I settled into a routine. I would walk up to the dhaba, making my way through a pagdandi (loose path) which was nestled amongst apple and apricot trees. It was the rainy season, and the entire mountain was lush green, with wildflowers accentuating the beauty of the mountains. The white wildflowers were a particular favourite - I’d love to gaze at them and the good old Rambo would love to smell and rub his nose in them.

My mornings started with a sweet pahadi chai with Aunty, as we sat leisurely outside the dhaba, doing something which only the pahadis know best - Dhoop Sekana. A practice which we are losing with urban living. I find it difficult to translate what Dhoop Sekana means - But imagine yourself sitting on a chatai or a chair in cold weather, in a verandah or on a terrace. It’s early morning and the sun has come up, gently beginning to warm your body. You’re enveloped by silence all around you, occasionally punctuated by the sounds of birds calling out to each other. A sense of coziness starts building. Time passes leisurely, and you sit without a care in the world.

As I sipped my tea, I often got into conversations with Aunty. She was curious about my life - of moving away from home for an education and a job, and how I was able to constantly switch cities every few years. Of how home was never a place, but the people who mattered in my life. I, in turn, was amazed by how they seemed to live completely off their land and were happy with so little.

And when I said this to her, she gave me a puzzled look and she said “What makes you think I have so little? I have everything that I need”

I was surprised, and I said - I am sure that you could do with a few more things, a few more comforts that would make your life easier. It would make you happier too.

And in the most normal way she said - Main santusht hoon (I am satisfied).

The one month of simple living in the Himalayas taught me the importance of satisfaction. I lived in a one-room cottage, with a single mattress, a chair and a bookshelf. One single bulb illuminated the room, and power cuts were the norm.

Despite being used to the comforts of urban living, all it took me was a few days to settle into a routine. Outside the first few days, being hard with this drastic change, I was able to find contentment in the slow pace of living.

And just as easily, once I returned to my regular life, I slipped back into my old patterns, unable to break out of my unhealthy habits, and yet somewhere Dolma Aunty’s voice stayed in my head.

We need the Axe of Satisfaction to cut through the Swallowing Evergreen Trees. Their evergreen desire to exploit us is only rivalled by our evergreen desire to give in. The Netflix documentary Buy Now! The Shopping Conspiracy tells us that this behaviour is deeply damaging to the world we live in.

Because the moment we find a sense of satisfaction, our need to elevate our status through overconsumption of objects and experiences will diminish. We will no longer have status anxiety and we will worry far less about how the world perceives us.

But even if we cut through Moradoom and emerge with a clear understanding of what satisfies us, we are going to run into another challenge.

Arriving at Igamor - The Disorienting Caves of Ignorance

Take a moment and reflect on your life. Think about where you grew up, who your early influences were, the schools and universities you went to, and the jobs you did. Remember the people who crossed paths with you, some stayed on, but most moved away.

If you had the typical Millennial experience that I did, you have lived through a time of one of the most rapid changes in human history. We leapt from the industrial age to the information age to ‘whatever this mess we live in’ is called. As humans, we became such a force of planetary change, that scientists are debating if we should coin it as an entirely new geological epoch called the Anthropocene.

The rapid change also brought in societal upheaval around the key pillars which define modern societies: Gender, Race and Religion. Closer home, we are living in a country, where as young women become more liberal, young men are turning more conservative, and even within this, North-Central vs South India differs. Men are increasingly finding it hard to understand and explain their position in the world and what masculinity means. Religion is a central tension point in Indian politics, and our class and caste struggles are nowhere near resolution. Even if you consider the urban elite of India (folks like you and me), who are insulated from the ‘Rest of India’, the economic anxiety is stifling. The Indian Millennial today is living under The Great Squeeze. We have been pushed to achieve everything in a short period, and are hyper-focused towards our goals. Goals that are physically, emotionally and economically crushing us.

Amidst all this, we are supposed to reconcile what we know (things we learnt growing up) with the new information that presents in front of us. But the new information comes in the form of an overload - too much, too complex and too dense to process. So what do we do?

The Greek philosopher Plato captured this conundrum well, which is known as the Allegory of the Cave. 1

Imagine a cave where people have been imprisoned from childhood. These prisoners are chained so that their legs and necks are fixed, forcing them to gaze at the wall in front of them and not to look around at the cave, each other, or themselves.

Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway with a low wall, behind which people walk carrying objects or puppets "of men and other living things"

The people walk behind the wall so their bodies do not cast shadows for the prisoners to see, but the objects they carry do. The prisoners cannot see any of what is happening behind them; they are only able to see the shadows cast upon the cave wall in front of them. The sounds of the people talking echo off the walls; the prisoners believe these sounds come from the shadows.

The shadows become reality.

Now suppose that the prisoner is released. A freed prisoner would look around and see the fire. The light would hurt his eyes and make it difficult for him to see the objects casting the shadows. If he were told that what he is seeing is real instead of the other version of reality he sees on the wall, he would not believe it.

In his pain, the freed prisoner would turn away and run back to what he is accustomed to.

When we are faced with something that genuinely challenges our worldview, we choose ignorance.

Caring only about the things which immediately affect us. Consuming only that which our senses can easily perceive.

We fall back on what we know, we revert to our biases. We make our known ignorance a source of truth.

And at its heart, this ignorance is disorienting.

So how do we get out of the cave?

Plato believes that the only way to escape the cave is to not privilege sensation but thought.

In our world obsessed with consumption of experiences and things, we have put ‘sensation’ on a pedestal, making it the hallmark of a life well lived.

We value things which appeal to our eyes, our nose, our tongue and our ears. Most of all, we privilege things which are best appreciated by our bodies.

Plato says that it is ideas, and not the material world known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality.

The simplest way to have ideas take centre stage in our lives, the smallest step we can take to escape the disorienting caves of ignorance is to annihilate the darkness of these caves with

The Torch of Curiosity.

The Woman who saved a Billion Lives

If you time travelled to the year 1923, specifically to the seaside town of Worthing in West Sussex, England, you would find two little girls pottering around with their portable mineral analysis kit. Their fascination was pebbles, and not completely by accident, because their parents were archaeologists in Egypt. One of the girls was named Dorothy, and in 1928, she joined her parents at the archaeological site of Jerash, in present-day Jordan, where she documented the patterns of mosaics from multiple Byzantine-era Churches dated to the 5th–6th centuries.

She spent more than a year finishing the drawings as she started her studies in Oxford, while also conducting chemical analyses of glass tesserae from the same site. She had developed a keen interest in chemistry, so much so, that on her 16th birthday her mother gave her a book by W. H. Bragg on X-ray crystallography, "Concerning the Nature of Things"

This book proved pivotal to her eventual interests. In 1932, Dorothy Hodgkin began a PhD at Cambridge, and it was then that she became aware of the potential of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of proteins. And her undying curiosity about the structure of things - from pebbles to proteins, found the catalyst that would soon shape the modern world - X-ray crystallography.

In the year 1945, Hodgkin and her colleagues, including biochemist Barbara Low, solved the structure of Penicillin, which went against all contemporary understanding of the antibiotic.

In 1948, Hodgkin first encountered one of the most structurally complex vitamins known to civilization. At the time, its structure was almost completely unknown, and when Hodgkin discovered it contained cobalt, she realized the structure actualization could be determined by X-ray crystallography analysis. The study published by Hodgkin was described as being as significant "as breaking the sound barrier". The vitamin is well known to the urban Indian elite, for so many of us are deficient in it - Vitamin B12.

But the crowning glory of her life came after a struggle of three decades, which started back in 1934.

The British organic chemist Robert Robinson offered a small sample of a crystalline hormone to Dorothy. The hormone captured her imagination because of the intricate and wide-ranging effect it has in the body. However, at this stage X-ray crystallography had not been developed far enough to cope with the complexity of the molecule. She and others spent many years improving the technique.

It took 35 years after taking her first photograph of the crystal for X-ray crystallography and computing techniques to be able to tackle larger and more complex molecules. Hodgkin's dream of unlocking the structure of that hormone was put on hold until 1969 when she was finally able to work with her team of young, international scientists to uncover the structure for the first time. The hormone we all know too well today.

Insulin

Hodgkin's work with insulin was instrumental in paving the way for insulin to be mass-produced and used on a large scale for treatment of both Type I and Type II diabetes.

Dorothy Hodgkin went from studying pebbles in streams to uncovering and understanding the nature of penicillin, vitamin B12 and insulin.

Work which has easily saved the life of a billion people2.

All driven by wielding the Torch of Curiosity.

Hodgkin solved her and our ignorance by constantly applying the torch of curiosity. And I’d happily assume if you’ve clicked on this piece and are still reading, you are a curious person.

So let us for a moment assume that you have not only cut through Moradoom - The evergreen forest of late stage capitalism, but have also escaped Igamor - The disorienting caves of ignorance.

But my friend, you are now caught right in the middle of Evermore.

Navigating Evermore - The River of Responsibilities

In 2013, Yitang Zhang, a former accountant who worked at a Subway franchise, called his wife “Pay attention to the media and newspapers”, he said. “You may see my name”

and she said

“Are you drunk?”

You should not blame Zhang’s wife. Every other man who walks this earth thinks his thoughts and ideas are stuff of genius. I don’t have data for this, but I have a strong feeling that many women would agree.

Zhang met his wife at a Chinese restaurant in Long Island, New York, where she was a waitress. He was born in Shanghai in 1955. His mother was a secretary in a government office, and his father was a college professor whose field was electrical engineering. As a small boy, he began “trying to know everything in mathematics,” he said. “I became very thirsty for math.”

His parents moved to Beijing for work, and Zhang remained in Shanghai with his grandmother. Mao’s Cultural Revolution had closed the schools. He spent most of his time reading math books that he ordered from a bookstore for less than a dollar.

Eventually, Zhang moved to Beijing to study at Peking University, China’s most respected school, and subsequently moved to Purdue University for his PhD. He earned his doctorate in 1991 and then disappeared from the mathematics scene.

He lived, sometimes with friends, in Lexington, Kentucky, where he had occasional work at a motel, and in New York City, where he also had friends and occasional work. Zhang found a job keeping the books at a Subway franchise. When Zhang wasn’t working, he would go to the library at the University of Kentucky and read journals in algebraic geometry and number theory. “For years, I didn’t really keep up my dream in mathematics,” he said.

In 1999, through the help of a friend, he secured a teaching position at the University of New Hampshire. He was still a nobody in the world of mathematics.

He rented an apartment about four miles from campus and rode to and from his office with students on a school shuttle. He said that he likes to sit on the bus and think.

Seven days a week, he arrived at his office around eight or nine and stayed until six or seven. The longest he had taken off from thinking was two weeks. Sometimes he woke up in the morning thinking of a math problem he had been considering when he fell asleep. Outside his office is a long corridor that he liked to walk up and down. Otherwise, he walked outside.3

The man took his routine more seriously than most of us do.

And you’d ask, what is so remarkable about that?

It’s remarkable because the call to his wife was not a drunk phone call. He was serious.

On April 17, 2013, without telling anyone, he sent a paper to Annals of Mathematics, widely regarded as the profession’s most prestigious journal. When the reviewers completed their review of it, they came back with the following comments

“We have completed our study of the paper ‘Bounded Gaps Between Primes’ by Yitang Zhang.” They went on, “The main results are of the first rank. The author has succeeded in proving a landmark theorem in the distribution of prime numbers.” And, “Although we studied the arguments very thoroughly, we found it very difficult to spot even the smallest slip. . . . We are very happy to strongly recommend acceptance of the paper for publication in the Annals.” 4

His paper was a back-door attack on the Twin Prime Conjecture, one of the greatest open problems in mathematics. It asserts that there are an infinite number of prime numbers that are only two numbers apart (Think 5 and 7, 11 and 13, the difference is always 2). Such pairs are more frequent at the beginning of the number line and less so among large numbers.

Zhang’s result did not prove that there are an infinite number of twin primes; rather, it gives a finite upper bound––70 million––for which the gaps between pairs of primes persist infinitely often.

Big deal, you’d say. The gap between 2 (the conjecture) and 70 million (what Zhang proved) is a factor of 35 million. But what we fail to account for is that the result is infinitely better than the gap between 2 and infinity. The people who had come closest to proving the twin-prime conjecture, had this to say

“What Zhang did was sensational. His work is a masterpiece. When you talk of number theory, a lot of the beauty is the machinery. Zhang somehow completely understood the situation, even though he was working alone. That’s how he surprised us.”

“Written with crystalline clarity and a total command of the topic’s current state of the art, he has proved one of the great results in the history of number theory.”

“He’s not a known expert, but he succeeded where all the experts had failed.”

Zhang is a classic example of the power of routine. Even in mathematical obscurity, he consistently went to the library and kept abreast of the developments in algebraic geometry and number theory. He worked every day - the same hours, at the same place, with little to no change in his routine. Zhang had finished “Bounded Gaps Between Primes” in late 2012; and then he spent a few months methodically checking each step, which he said was “very boring.”

Zhang’s work was never about the hustle culture which envelopes and consumes us, just like the swallowing trees of Moradoom do. His routine is a beautiful poem, pithy with a clear message - Consistency over Flashes of Brilliance. Repeatability over Spontaneous Genius.

In our lives, we are all wading through Evermore - The River of Responsibilities. At any given point, a million things are running in our heads, and if you are a woman, more so. Everything from kids to money to water heater repairs to the worst question every adult has to answer, “What are we going to eat today?”

To navigate the river of responsibilities, we need the

Oars of Routine

Navigating the river of responsibilities needs tact - One cannot go against the flow for too long. When your child needs attention in a meaningful way, you need to be present. When that presentation deadline is looming, you need to hunker down and get the work done. But if we are to stop and observe the cadence of our lives, we will notice the patterns - How responsibilities pile up around certain times of the day/week/month or year. How we are repeatedly making predictable, poor choices, taking suboptimal decisions consistently.

All of these can be navigated with the oars of routine.

Routines are amazing in one single way - They take away the need to make decisions. Decisions about mundane things, which need to be made in a short amount of time. Our dopamine hungry, stress addled brains are being asked to do too much, too often. A carefully crafted routine will free up both physical time and mental space to allow for our curiosity to thrive.

Because after cutting through Moradoom with the Axe of Satisfaction, escaping Igamor with the Torch of Curiosity and navigating Evermore with the Oars of Routine, we finally arrive at the starting point of our destination.

Arriving at Luminspire - The Mountains of Knowledge

You’re here. And ahead of you lies an entire mountain range. As far as the eye can see, you can see peaks one after the other. You look around and realise you are on a peak yourself. How did you get here?

By doing what you have been doing for years. Each of us, by accident or by choice, has picked out a career or an area to work in. Working with a multitude of people, clients and partners in that area, you have developed an expertise in it. So much so, that it comes naturally to you, and you sometimes forget to consider it as a valued skill. You use it effortlessly at work and advise younger folks who are trying to grow their knowledge in the space. Your skill drives considerable impact, and you are rightfully an expert in that space.

And as you stand on the peak, you can make out that other experts are standing on other peaks. Peaks you know something about, peaks you have just heard of and peaks you did not even know existed. You try and shout to communicate with them, but they cannot hear you. Your voice merely echoes, ricocheting off the surface of the mountain. You’d like to get onto another peak, speak to the expert sitting on it. You want to engage them in conversation and learn from them, but it would require you to do something hard.

Get off your peak.

Because getting off your peak would mean going through the discomfort of abandoning all notions of knowledge, and being willing to become a student again. You will need to accept that you know nothing about this new peak.

Thomas Szasz, a Hungarian-American psychiatrist, once remarked

Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one's self-esteem.

That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily; and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.

We all need to come down from our peaks. For us to truly learn something, we need to abandon our views about it. Because the act of coming down from the peak forces us to do three things

Understand the limits of our thinking: As we come down, and shed our views, we start seeing our field of knowledge more objectively, and understand that there are limits to our thinking, even though we are experts.

Open space for contemplation: Once we come down, and make our way to another peak, we start walking, which opens the space for contemplation.

Isolate ourselves from our ego: Once we have stripped ourselves of our views, and contemplated, we isolate ourselves from our Ego. This act of isolation humbles us, makes us realise our follies and helps us see illusions we have lived under.

And once you do that, you possibly put yourself on a path, on which Paul Erdős walked for decades.

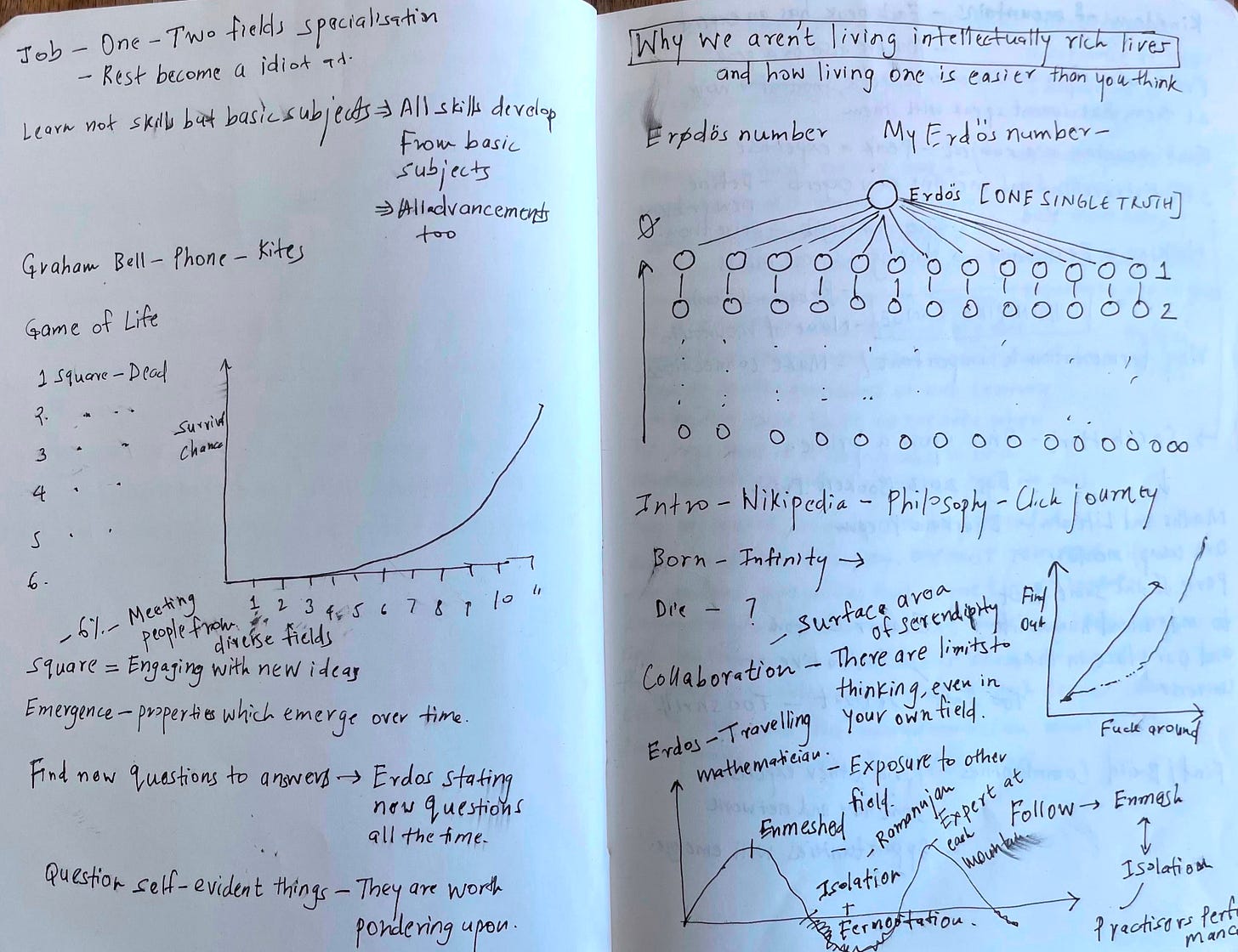

Paul Erdős - The World’s Most Influential Mathematician you’ve never heard of

Imagine being so prolific and collaborative, that the mathematical community comes together to name a number after you - Erdős number. No, not the kind of constants we had to mug up in physics and chemistry. Not Avogadro’s number or the value of gravity at the surface of the earth.

Sample this.

An Erdős number describes a person's degree of separation from Erdős himself, based on their collaboration with him, or with another who has their own Erdős number. Erdős alone was assigned the Erdős number of 0 (for being himself), while his immediate collaborators could claim an Erdős number of 1, their collaborators have Erdős number at most 2, and so on.

Approximately 200,000 mathematicians have an assigned Erdős number, and some have estimated that 90 percent of the world's active mathematicians have an Erdős number smaller than 8.

Imagine, for a second, that 90% of the people in your field are connected with you via collaborators.

He worked with more than 500 collaborators. He firmly believed mathematics to be a social activity, living an itinerant lifestyle with the sole purpose of writing mathematical papers with other mathematicians. He devoted his waking hours to mathematics, even into his later years; he died at a mathematics conference in Warsaw in 1996.

Time magazine called him "The Oddball's Oddball".

Possessions meant little to Erdős; most of his belongings would fit in a suitcase. Awards and other earnings were generally donated to people in need and various worthy causes. He spent most of his life traveling between scientific conferences, universities, and the homes of colleagues worldwide. He earned enough stipends to fund his travels and basic needs as a guest lecturer at universities and from various mathematical awards.

He would typically show up at a colleague's doorstep and announce "my brain is open", staying long enough to collaborate on a few papers before moving on a few days later. In many cases, he would ask the current collaborator about whom to visit next.

After his mother died in 1971, he started taking antidepressants and amphetamines. His friend, the American mathematician, Ron Graham bet him $500 that he could not stop taking them for a month.

Erdős won the bet but complained that it impacted his performance: "You've showed me I'm not an addict. But I didn't get any work done. I'd get up in the morning and stare at a blank piece of paper. I'd have no ideas, just like an ordinary person. You've set mathematics back a month."

After he won the bet, he promptly resumed his use of antidepressants and amphetamines.

Overall, his work leaned towards solving previously open problems, rather than developing or exploring new areas of mathematics. Erdős published around 1,500 mathematical papers during his lifetime, a figure that remains unsurpassed.5

Erdős was so prolific because he collaborated. He was aware of the limits of his knowledge, and actively sought collaborators to move mathematics ahead. He was willing to let go of his ego and enmesh himself with other experts.

He was willing to get down from his peak, walk, and climb the next peak. And do it all over again. Over an entire lifetime.

So in a life, where meeting new people and making new friends is hard in your 30’s and 40’s, how could you possibly find experts and collaborators? When each of us is enmeshed in our fields and sub-fields, how are we to isolate and enmesh ourselves with others?

Building and Finding Communities

On 8th April 2024, Deepak ‘Chuck’ Gopalakrishnan and I started a little experiment. We launched The 6% Club, where we hoped to help people launch their newsletters, podcasts or YouTube channels. We expected 10 people to sign up.

80 did.

We had to limit the size of the cohort to 40, and open another cohort in July, which had to accommodate the other 40. And while we were thrilled to have such an overwhelming response, we did not even anticipate the hidden benefits we would accrue.

How often do you meet smart, thoughtful, empathetic and creative people?

How often do you meet them, 40 at a time?

How often do you meet a fresh set of 40, four times a year?

Over the past year, across four cohorts, we have had the privilege to intimately know 150+ such people. I am floored by the dumb luck we are experiencing - Just as a sample: We have mentored wildlife photographers, physicians, scientists, painters, professors and ultramarathoners. Even someone who has an Erdős number of 2. We have mentored people who have gone through life-changing trauma, and have subsequently turned their life around (which btw is deeply embarrassing because what can I teach them?). We have had the privilege of seeing thoughtful newsletters, vulnerable podcasts and beautiful YouTube channels come to life. And we can claim a tiny piece of credit for them.

Everyday, I get the opportunity to climb down from my peak, and ask these folks elementary questions, and have them indulge me with an equanimity only surpassed by the experts facing Philomena Cunk.

Everyday, I get the privilege of having these people being one message or call away. I could even call some of them, friends.

You may not be at a point in life to be able to build such a community. But you can find experts and collaborators. Here is how you could do it

Define 1-2 areas you’d want to learn about. Something you have been genuinely curious about, ideally for a long time.

Ask EVERYONE you know - Hey, I am interested in learning about Y. Do you know someone who knows a lot about Y?

Once you find a connection, ask for a warm introduction. I can almost guarantee you, the expert will be happy to give you their time.

Ask thoughtful questions. Don’t expect them to explain things to you, but ask them to point you to resources, or craft a learning path with them.

Put in the hours, immerse yourself in the resources and update them about the progress you have made and the things you have learnt.

This in turn will start a conversation.

Repeat 1 - 6 for the rest of your life.

And what will happen?

You have kickstarted your own version of ‘The Game of Life’. Remember, the Game of Life has only one variable: The starting point. You now have not just ideas from your field, but ideas from fields you know nothing about. You will now see ‘emergence’ in action.

I’ve experienced this first hand. Take this Substack for example. My initial pieces were in the style I typically wrote in - Text, with a few images. Then, through one of the cohort members of The 6% Club, I was introduced to the writings of More to That. A few years earlier, thanks to an early conversation with Nishant Jain (aka SneakyArtist), who encouraged me to sketch, I got over my fears and picked up sketching with a pen. How did I discover him? By listening to him on Amit Varma’s The Seen and The Unseen. I just reached out to him, and got a conversation going. I showed him my early sketches and he gave me feedback. I sought another expert in Khushboo Prashant whose course taught me the basics of linework. With her kindness and patience, she gave me extensive feedback on my sketching (and all of them gave me faith in the generosity of experts).

Combined with my existential questions, pieces like these (and the last three, here, here and here) were born. I take inspiration (which includes me trying to copy their style and fail) from multiple artists for the linework and sketches you see in the pieces. Now with this one, I tried my hand at drawing a fantasy map, coming up with names for all the places (which I could not, and my fantasy fiction loving partner did). I have used watercolours extensively to bring the map alive, and I will let you decide how good/bad/ugly it is.6

Could I have elevated my writing without all these experts? Not a chance in hell. They may not be my collaborators today, but who knows what the future holds?

The unknowability of a future filled with the potential of giving birth to new ideas and projects is what makes life worth living.

So there you have it - The key to living an intellectually rich life. But there is one step missing.

Document your intellectual journey

Write physically in a journal, write on your phone, write on your laptop. Write on whatever latest gadget you’ve gotten your hands on.

Write notes, single line ideas, thoughts, quotes. Doodle, sketch, paint. Write entire pieces in long form, by hand.

Write for no one but yourself. The act of writing forces you to think clearly. It makes you commit your ideas to paper in a logical flow. It allows you to make connections you did not see earlier. It allows you to come up with ideas that seemed implausible. Writing is emergence, of the ideas and the self.

It does not have to follow a pattern. It does not have to make sense. I blend lived experience, mathematics and science with philosophy, and sprinkle it with some art.

Why do I mix the two?

Because the arts and the sciences are not different. As Sarah Hart, the eclectic author of Once Upon a Prime says

Math and Literature are complementary parts of the same quest: To understand human life and our place in the universe.

You will find your formula too. You have to trust the process7

After all, aren’t we all trying to understand our place in the universe?

Thank you for reading this far. I am grateful that you gave me 30 minutes of your time. I hope some part of this made you feel heard or helped you feel, think and live better.

I have one last thing to say. I along with a friend run The 6% Club, a content creation program designed for people with full-time jobs. We help you launch your newsletter, podcast or YouTube channel in 45 days. We neither promise virality nor algorithm hacking, but a sustainable, enjoyable way to build a creative outlet for yourself. We have helped 150+ people so far and could help you too.

The explanation of Plato’s Allegory for the Cave is sourced from the Wikipedia page

Minor footnote: Dorothy Hodgkin also won the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, and is the only British woman scientist to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in any of the three sciences it recognizes.

The story about the early part of Zhang’s life has been sourced from his profile in the New Yorker - The Pursuit of Beauty

If you have read past editions of this newsletter, you’d have realised by now that I am kind of obsessed with mathematics and prime numbers.

The profile of Paul Erdős has been sourced from his Wikipedia page

The paper on which the map is drawn was white to begin with. I treated it with coffee to bring out an old, browned out effect. And then got so enamoured with water colours, that the effect is almost invisible

I may have borrowed this line from my Yoga teacher, another expert.

Loved this piece..what I would like to learn from you is not how to start a newsletter but fundamentally how to write so well...how you have combined chemistry, math and philosophy..If you don't mind..what is your educational background to know all these different fields in such depth...if you come up with a course on writing, I will definitely sign up :)

I chose to listen to this essay rather than read it, and felt like I was on an actual journey through the lands you've conjured up. One part of my brain was visualising the soul-sucking allure of the evergreens, another was smiling at the idea of you and Rambo walking through the fruit trees, yet another about the "oddball" life of Paul Erdos, about whom I had never heard of. I love how you have woven different ideas and thought strands together to create a map (in this case, also literally). Possibly your best piece yet, Utsav.